Who Was Killed in America's Drug War Last Year? [FEATURE]

For the past two years, Drug War Chronicle has been tracking all the US deaths directly attributable to domestic drug law enforcement, including the border. You can view the 2011 deaths here and the 2012 deaths here.Soon, we will hand our findings out to criminal justice and other professionals and then issue a report seeking to identify ways to reduce the toll. In the meantime, we can look at the raw numbers from last year and identify some trends.

We also used fairly tight criteria for inclusion. These deaths had to have occurred during drug law enforcement activities. That means people whose deaths may be at least partially blamed more broadly on drug prohibition (overdoses, AIDS and Hepatitis C victims, for example) are not included. Neither are the deaths of people who may have been embittered by previous drug law enforcement operations who later decide to go out in a blaze of glory, nor the deaths of their victims.

It's only people who died because of drug law enforcement. And even that is something of a grey area. One example is traffic stops. Although they ostensibly are aimed at public safety, drug law enforcement is at least a secondary consideration and, sometimes, as in the case of "pretextual stops," the primary consideration, so we include those deaths when it looks appropriate. Another close call was the case of a Michigan father accused of smoking marijuana and reported to Child Protective Services by police. He was shot and killed in a confrontation with police over that issue. We included him even though it was not directly drug law enforcement that got him killed, but the enforcement of child custody orders related to marijuana use. It could be argued either way whether he should not have been included; we decided to include him.

Because we are a small nonprofit with limited resources, we have been unable to follow-up on many of the cases. Every law enforcement-related death is investigated, but those findings are too often unpublished, and we (I) simply lack the resources to track down the results of those investigations. That leaves a lot of questions unanswered -- and some law enforcement agencies and their personnel, and maybe some others, off the hook.

We attempted to provide the date, name, age, race, and gender of each victim, but were unable to do so in every case. We also categorized the type of enforcement activity (search warrant service, traffic stops, undercover buy operations, suspicious activity reports, etc.), whether the victim was armed with a firearm, whether he brandished it, and whether he shot it, as well as whether there was another type of weapon involved (vehicle, knife, sword, etc.) and whether the victim was resisting arrest or attempting to flee. Again, we didn't get all the information in every case.

Here's what we found:

In 2012, 63 people died in the course of US domestic drug law enforcement operations, or one about every six days. Eight of the dead were law enforcement officers; 55 were civilians.

Law Enforcement Deaths

The last drug war death of the year, on December 14, was that of Memphis police officer Martoiya Lang, who was shot and killed serving a "drug-related search warrant" as part of an organized crime task force. Another officer was wounded, and the shooter, Trevino Williams, has been charged with murder. The homeowner was charged with possession of marijuana with intent to distribute.

In between Francom and Lang, six other officers perished fighting the drug war. In February, Clay County (Florida) Sheriff's Detective David White was killed in a shootout at a meth lab that also left the suspect dead. In April, Greenland, New Hampshire, Police Chief Michael Maloney was shot in killed in a drug raid that also left four officers wounded. In that case, the shooter and a woman companion were later found dead inside the burnt out home.

In June, Puerto Rican narcotics officer Victor Soto Velez was shot and killed in an ambush as he sat in his car. Less than two months later, Puerto Rican police officer Wilfredo Ramos Nieves was shot and killed as he participated in a drug raid. The shooter was wounded and arrested, and faces murder charges.

Interdicting drugs at the border also proved hazardous. In October, Border Patrol Agent Nicholas Ivie was shot and killed in a friendly fire incident as he and other Border Patrol agents rushed to investigate a tripped sensor near the line. And early last month, Coast Guard Chief Petty Officer Terrell Horne III was killed when a Mexican marijuana smuggling boat rammed his off the Southern California coast. Charges are pending against the smugglers.

Civilian Deaths

Civilian deaths came in three categories: accidental, suicide, and shot by police. Of the 55 civilians who died during drug law enforcement operations, 43 were shot by police. One man committed suicide in a police car, one man committed suicide in his bedroom as police approached, and a man and a woman died in the aftermath of the Greenland, New Hampshire, drug raid mentioned above, either in a mutual suicide pact or as a murder-suicide.

Five people died in police custody after ingesting packages of drugs. They either choked to death or died of drug overdoses. One man died after falling from a balcony while fleeing from police. One man died in an auto accident fleeing police. One Louisville woman, Stephanie Melson, died when the vehicle she was driving was hit by a drug suspect fleeing police in a high-speed chase on city streets.

The Drug War and the Second Amendment

Americans love their guns, and people involved with drugs are no different. Of the 43 people shot and killed by police, 21 were in possession of firearms, and in two cases, it was not clear if they were armed or not. Of those 21, 17 brandished a weapon, or displayed it in a threatening manner. But only 10 people killed by police actually fired their weapon. Merely having a firearm increased the perceived danger to police and the danger of being killed by them.

In a handful of cases, police shot and killed people they thought were going for guns. Jacksonville, Florida, police shot and killed Davinian Williams after he made a "furtive movement" with his hands after being pulled over for driving in a "high drug activity area." A month later, police in Miami shot and killed Sergio Javier Azcuy after stopping the vehicle in which he was a passenger during a cocaine rip-off sting. They saw "a dark shiny object" in his hand. It was a cell phone. There are more examples in the list.

Several people were shot and killed as they confronted police with weapons in their own homes. Some may have been dangerous felons, some may have been homeowners who grabbed a gun when they heard someone breaking into their homes. The most likely case of the latter is that of an unnamed 66-year-old Georgia woman shot and killed by a local drug task doing a "no knock" drug raid at her home. In another case from Georgia, David John Thomas Hammett, 60, was shot and killed when police encountered him in a darkened hallway in his home holding "a black shiny object." It was a can of pepper spray. Neither victim appears to have been the target of police, but they're still dead.

Police have reason to be wary of guns. Of the eight law enforcement officers killed enforcing the drug laws last year, seven were killed by gunfire. But at least 22 unarmed civilians were shot and killed by police, and at least four more were killed despite not having brandished their weapons.

It's Not Just Guns; It's Cars, Too

In at least seven cases, police shot and killed people after their vehicles rammed police cars or as they dragged police officers down the street. It is difficult to believe that all of these people wanted to injure or kill police officers. Many if not most were probably just trying to escape. But police don't seem inclined to guess (which might be understandable if you're being dragged by a moving car.)

Getting killed in the drug war is mostly a guy thing. Of the 63 people killed, only six were women, including one police officer. One was the Georgia homeowner, another was the Louisville woman driver hit by a fleeing suspect, a third was the unnamed woman who died in the Greenland, New Hampshire raid. Other than the Memphis police officer, only two women were killed because of their drug-related activities.

Getting killed in the drug war is mostly a minority thing too. Of the 55 dead civilians, we do not have a racial identification on eight. Of the remaining 47, 23 were black, 14 were Hispanic, nine were white, and one was Asian. Roughly three out four drug war deaths were of minority members, a figure grossly disproportionate to their share of the population.

Bringing Police to Justice

Many drug war deaths go unnoticed and un-mourned. Others draw protests from friends and family members. Few stir up public outrage, and fewer yet end up with action being taken against police shooters. Of the 55 civilians who died during drug law enforcement activities, charges have been filed against the police shooters in only two particularly egregious cases. Both cases have generated significant public protest.

One is the case of Ramarley Graham, an 18-year-old black teenager from the Bronx. Graham was chased into his own apartment by undercover NYPD officers conducting drug busts on the street nearby. He ran into his bathroom, where he was apparently trying to flush drugs down the toilet, and was shot and killed by the police officer who followed him there. Graham was unarmed, police have conceded. A small amount of pot was found floating in the toilet bowl. Now, NYPD Officer Richard Haste, the shooter, has been indicted on first- and second-degree manslaughter charges, with trial set for this coming spring.

The other case is that of Wendell Allen, 20, a black New Orleans resident. Allen was shot and killed when he appeared on the staircase of a home that was being raided for marijuana sales by New Orleans police. He was unarmed and was not holding anything that could be mistaken for a weapon. Officer Jason Colclough, the shooter, was indicted on manslaughter charges in August after he refused a plea bargain on a negligent homicide charge. When he will go to trial is unclear.

Criminal prosecutions of police shooters, even in egregious cases, is rare. Winning a conviction is even less unlikely. When Lima, Ohio, police officer Joe Chavalia shot and killed unarmed Tanika Wilson, 26, and wounded the baby she was holding in her arms during a SWAT drug raid in 2008, he was the rare police officer to be indicted. But he walked at trial.

It doesn't usually work out that way when the tables are turned. Ask Corey Maye, who was convicted of murder and sentenced to death for killing a police officer who mistakenly entered his duplex during a drug raid even though he argued credibly that he thought police were burglars and he acted in self defense. It took 10 years before Maye was able to first get his death sentence reduced to life, then get his charges reduced to manslaughter, allowing him to leave prison.

Or ask Ryan Frederick, who is currently sitting in prison in Virginia after being convicted of manslaughter in the 2008 death of Chesapeake Det. Jarrod Shivers. Three days after a police informant burglarized Frederick's home, Shivers led a a SWAT team on a no-knock raid. Frederick shot through the door as Shivers attempted to break through it, killing him. He argued that he was acting in self-defense, not knowing what home invaders were on the other side of the door, but in prison he sits.

Both the Graham and the Allen cases came early in the year. Late in 2012, two more cases that would appear to call out for criminal prosecutions of police occurred. No charges have been filed against police so far in either case.

On October 25, undocumented Guatemalan immigrants Marco Antonio Castro and Jose Leonardo Coj Cumar were shot and killed by a Texas Department of Public Safety trooper who shot from a helicopter at the pickup truck carrying them as it fled from an attempted traffic stop. Texas authorities said they thought the truck was carrying drugs, but it wasn't -- it was carrying undocumented Guatemalan immigrants who had just crossed the border. Authorities said they sought to disable the truck because it was "traveling at reckless speeds, endangering the public." But the truck was traveling down a dirt road surrounded by grassy fields in an unpopulated area. The Guatemalan consulate and the ACLU of Texas are among those calling for an investigation, and police use of force experts from around the country pronounced themselves stunned at the Texas policy of shooting at vehicles from helicopters. Stay tuned.

Two weeks later, undercover police in West Valley, Utah, shot and killed Danielle Misha Leonard, 21, in the parking lot of an apartment building. Leonard, a native of Vancouver, Washington, had been addicted to heroin and went to Utah to seek treatment. Perhaps it didn't take. Police have been extremely slow to release details on her killing, but she appears to have been unarmed. An undercover police vehicle had boxed her SUV into a parking spot, and the windshield and both side windows had been shattered by gunfire. Later in November, in their latest sparse information release on the case, police said only that she had been shot twice in the head and that they had been attempting to contact her in a drug investigation. Friends and family have set up a Justice for Danielle Willard Facebook page to press for action.

Now, it's a new year, and nobody has been killed in the drug war so far. But this is only day two.

First Private Marijuana Clubs Open in Colorado

At least two members-only recreational marijuana clubs opened in Colorado Monday, one in Denver and one in the small southern Colorado town of Del Norte, according to the Associated Press. The club openings come less than a month after Gov. John Hickenlooper certified the results of the November vote on Amendment 64, which legalized for adults 21 and over the possession of up to an ounce and the cultivation of up to six pot plants.

In Denver, Club 64 opened Monday afternoon, less than 24 hours after organizers announced they would create it. It already had 200 members, who had shelled out $29.99 each for the privilege of joining. The club, which will meet monthly at different locations, will charge the same fee each month.

"It's just a place for adults to exercise their constitutional rights together," Denver marijuana attorney Rob Corry told the AP. "We're not selling pot here."

As reggae blasted from speakers below a glittering disco ball and "The Big Lebowski" played on a wall screen, club members shared puffs and hugs as they gathered to celebrate the new year and the new era.

"Look at this!" club organizer Chloe Villano excitedly told the AP. "We were so scared because we didn't want it to be crazy. But this is crazy! People want this."

Not every marijuana reformer in Colorado is on board, according to a CNN report published New Year's Day. "Much of our success with Amendment 64 was making the soccer moms comfortable," an advocate told CNN, adding, "This is not the fight we want to have right now." The advocate spoke anonymously, in order to avoid creating a rift in the community, according to the CNN report.

In Del Norte, the Whitehorse Inn opened Monday afternoon, becoming the first private marijuana club in the state. But according to the Denver Post, publicity surrounding the opening resulting in owner Paul Lovato losing his lease. While Lovato had the keys to the property, his lease didn't actually start until Tuesday, and when the landlord saw the publicity, he canceled the lease before it went into effect.

"By opening early I kind of screwed myself out of my building," Lovato said Tuesday.

He had planned to open at midnight Monday, just after New Year's Eve ticked over to New Year's Day, but moved up his opening by a few hours after hearing about Club 64. Lovato wanted to be first.

"It was really unexpected," he said of the lease cancelation. "I got caught up in the whole 'I want to be the first to open' thing. And I did that. I was the first... I'm pretty proud of that."

If Lovato has lost his location, he hasn't lost his club. He said he was expecting visitors from nearby New Mexico to show up Tuesday.

"We're doing the White Horse Inn at my house today," he said.

America now has its first legal marijuana dens.

Florida Must Pay Attorney Fees in Employee Drug Test Lawsuit

A federal judge has ordered the state of Florida to pay more than $190,000 in attorneys' fees in a case challenging an executive order ordering suspicionless drug testing of state employees issued last year by Gov. Rick Scott (R). Those taxpayer funds have now been lost to Scott's chimeric crusade to impose drug testing on various fronts.

A report by the Orlando Sentinel found that the state has now incurred over a million dollars in legal bills for controversial legislation pushed by the governor.

Judge Ungaro had ruled that Scott's executive order was unconstitutional back in April, saying the governor did not show a "compelling need" to impose drug testing. Scott has appealed to the 11th US Circuit Court of Appeals.

Scott's drug testing plan has never been implemented except among some employees of the Department of Corrections. He put it on hold because of the legal challenge.

Another of Scott's pet projects, the mandatory suspicionless drug testing of welfare applicants and recipients has also been so far stymied in the federal courts. In that case, a federal judge issued a temporary injunction blocking implementation amid strong hints she would eventually rule that the practice was unconstitutional.

Meanwhile, despite the legal roadblocks -- and financial costs to taxpayers of fighting them -- Scott and the legislature last year passed another bill, House Bill 1205, which would allow, but not require, state agencies to conduct random suspicionless drug testing of state workers. That law, too, is on hold as it faces challenges in the federal courts.

Medical Marijuana Update

It's been fairly quiet over the holidays, but medical marijuana is legal in Massachusetts now! Let's get to it:

California

On December 19, the Berkeley Patients Group dispensary reopened for business. The longtime community stalwart was forced to shut down at its former location after asset forfeiture threats to its landlord by federal prosecutors. Ever since it was forced to close its doors last spring, it operated as a delivery service, but now it is a storefront dispensary again, and it's just a block and a half down San Pablo Avenue from its former location.

On December 20, a Solano County Superior Court judge threw out cases against two Vallejo dispensary operators. The two men, Jorge Espinoza, 25, and Jonathan Linares, 22, had been charged with marijuana possession and sale, and operating an illegal dispensary. Their dispensary, the Better Health Group collective, had been raided by Vallejo police three times and closed down after the third raid in June. Judge William Harrison dismissed the charges, saying after the ruling that dispensaries that comply with the Compassionate Use Act and the Medical Marijuana Program Act are allowed to operate. This was the first in a number of Vallejo dispensary cases resulting from a police crackdown last year. The police crackdown came months after Vallejo voters approved an initiative to tax dispensaries.

On December 21, attorneys for Mendocino County filed a motion to quash federal subpoenas seeking "records, letters and any other communications on the Mendocino County Medical Marijuana Cultivation Regulation to include third-party inspectors and the Mendocino County Board of Supervisors" since January 1, 2010. The request was expanded to include all "memoranda, notes, files, or records relating to meetings or conversations concerning" the Zip Tie program or Medical Marijuana Cultivation Regulation. The county argues that "the scope of the subpoenas is overbroad and burdensome, oppressive, and constitutes an improper intrusion into the ability of state and local government to administer programs for the health and welfare of their residents." No court date has been set to hear the motion. The county has until January 8 to comply with the subpoena.

Last Tuesday, the Oroville Planning Commission approved a new medical marijuana growing ordinance that will go before the city council for final approval. The ordinance would require that crops be grown indoors in secured structures and that anyone growing get a permit from the city. To legally grow medical marijuana inside the city, a qualified person must apply for a permit, meet all the requirements and have the growing facilities inspected by the police chief or a person designated by the police chief. The permit will be issued by the police chief or his or her designee.

Massachusetts

On December 22, state Sen. John Keenan called for a delay in implementing the state's new medical marijuana law. Keenan also said he would introduce legislation that would "close loopholes" by imposing controls beyond those approved by the voters, including eliminating home cultivation, requiring marijuana "prescriptions" to be entered in the state's Prescription Monitoring Program to avoid "doctor shopping."

On Tuesday, medical marijuana became legal in Massachusetts as voter-approved Question 3 went into effect. But it will be months before any dispensaries open. The Department of Public Health has until May 1 to develop regulations.

Michigan

On December 19, the state Supreme Court ruled that collective grows are not allowed under the state's medical marijuana law. The ruling came in the case of Ryan Bylsma, a Grand Rapids man who gave others warehouse space to grow. Bylsma is a state-approved caregiver who could grow 24 plants for two people, but he also allowed other caregivers and patients to grow in the same space. When he was raided, there were 88 plants in the warehouse. Kent County authorities said that arrangement was illegal and charged him with manufacturing marijuana. The court agreed, arguing he "exercised dominion and control over all the plants in the warehouse space that he leased, not merely the plants in which he claimed an ownership interest." The Supreme Court sent the case back to Kent County to allow Bylsma to offer an alternative defense.

Vermont

On Monday, the select board in Rutland decided not to prohibit dispensaries. No one has applied to open one, but board members agreed they shouldn't be banned.

Washington

On December 19, the Everett city council banned collective gardens. It declared medical marijuana a nuisance with an order that will expire in 18 months. The vote came ahead of the expiration of the city's moratorium on collective gardens and effectively continues it. Medical marijuana patients set the ban could lead to legal action against the city.

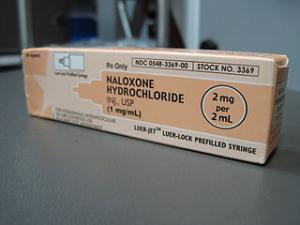

Naloxone Cheap Way to Prevent Drug OD Deaths, Study Finds

Drug overdose deaths are now the leading cause of accidental death in the US, surpassing automobile accidents, but a new study suggests that distributing naloxone to opioid drug users could reduce the death toll in a cost-effective manner. The study was published this week in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

At least 183 public health programs around the country have trained some 53,000 people in how to use naloxone. These programs had documented more than 10,000 cases of successful overdose reversals.

In the study published in the Annals, researchers developed a mathematical model to estimate the impact of more broadly distributing naloxone among opioid drug users and their acquaintances. Led by Dr. Phillip Coffin, director of Substance Use Research at the San Francisco Department of Public Health, and Dr. Sean Sullivan, director of the Pharmaceutical Outcomes Research and Policy Program at the University of Washington, the researchers found that if naloxone were available to 20% of a million heroin users, some 9,000 overdose deaths would be prevented over the users' lifetimes.

In the basic research model, one life would be saved for every 164 naloxone kits handed out. But using more optimistic assumptions, naloxone could prevent as many as 43,000 overdose deaths, saving one life for every 36 kits distributed.

Providing widespread naloxone distribution would cost about $400 for every year of life saved, a figure significantly below the customary $50,000 cut-off for medical interventions. That's also cheaper than most accepted prevention programs in medicine, such as checking blood pressure or smoking cessation.

"Naloxone is a highly cost-effective way to prevent overdose deaths," said Dr. Coffin. "And, as a researcher at the Department of Public Health, my priority is maximizing our resources to help improve the health of the community."

Naloxone has proven very effective in San Francisco, with heroin overdose deaths declining from 155 in 1995 to 10 in 2010. The opioid antagonist has been distributed there since the mid-1990s, and with the support of the public health department since 2004. But overdose deaths for opioid pain medications (oxycodone, hydrocone, methadone) remain high, with 121 reported in the city in 2010. Efforts are underway in the city to expand access to naloxone for patients receiving prescription opioids as well. This study is the latest to suggest that doing so will save lives, and do so cost-effectively.

German Court Approves Some Medical Marijuana Growing

A German court ruled in December that seriously ill patients can grow their own medicine, but the ruling won't apply to all medical marijuana patients. The Federal Administrative Court in Munster held that people for whom no other effective remedies are available or affordable can apply to the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (BfArM) for a license to grow their medicine if done under a doctor's supervision.

"If an affordable treatment option is missing, a license for personal cultivation of cannabis has to be taken into consideration -- at the discretion of the BfArM," the court ruled, according to an account in Deutsche Welt.

The decision was welcomed by medical marijuana advocates.

"This ruling is a milestone on the path to a better supply of German citizens with cannabis-based medicines," said Franjo Grotenhermen, chairman of the German Association for Cannabis as Medicine in remarks published in Deutscher Hanfverband, which covers German marijuana issues. "Cannabis products from the pharmacy are unaffordable for most patients. Legalized growing of the plant at home opens up for them for the first time an affordable alternative."

The decision does not apply to patients whose insurance covers the cost of marijuana-based medications, the court clarified. But many health insurance companies refuse to reimburse the cost of those treatments. Other insurance companies will pay for Marinol, but some patients find it less effective than herbal marijuana. Those patients are also out of luck.

Currently, patients can be prescribed Marinol or the tincture Sativex, or they can apply to the BrAfM for permission to import prescription marijuana from the Netherlands.

"It is unbearable that many patients have to rely on illegal sources or illegal self-cultivation of their medical need," Grotenhermen said.

Now, the federal government will have to respond to the court's decision, said Dr. Oliver Tolmein, who represented the plaintiff, a multiple sclerosis sufferer identified only by his first name and last initial.

"If the Ministry of Health does not want patients to grow cannabis for self-therapy, is has to be made absolutely clear in the law on health insurances that they have to reimburse the cost of cannabinoid-containing medicines or medicinal cannabis for otherwise untreatable patients," he told Deutscher Hanfverband.

This Week's Corrupt Cops Stories

Philadelphia keeps on paying for its out-of-control drug squad, and a pair of probation officers have pill-pilfering problems. Let's get to it:

In Madison, Wisconsin, a former probation agent was charged December 20 with stealing prescription drugs from probationers. Kim Hoenisch, 41, who worked in the Department of Corrections' Wausau office, is accused of stealing Vicodin pills from probationers when they showed up for urine tests during office visits, stealing Vicodin from a probationer's home, stealing Vicodin from her cousin's house, and stealing oxycodone from another woman's house. She faces multiple charges, including felony drug possession and misconduct in office.

In Casper, Wyoming, a former state probation officer pleaded guilty December 20 to charges she stole prescription drugs from probationers. Ruby Mattox, 34, admitted repeatedly intentionally spilling her probationers' pill bottles and pocketed some of the pills as she picked them up. She also stole an entire bottle of prescription pills from an acquaintance and embezzled money collected by coworkers for a fundraising event. In a plea bargain, she pleaded guilty to four misdemeanor theft counts and one felony count of drug possession. She will be sentenced at a later date, but will avoid prison time as part of the plea bargain.