Consequences of Prohibition

Drug War Issues

Drug overdose deaths are now the leading cause of accidental death in the US, surpassing automobile accidents, but a new study suggests that distributing naloxone to opioid drug users could reduce the death toll in a cost-effective manner. The study was published this week in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

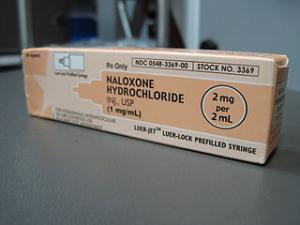

Naloxone package (wikimedia.org)

At least 183 public health programs around the country have trained some 53,000 people in how to use naloxone. These programs had documented more than 10,000 cases of successful overdose reversals.

In the study published in the Annals, researchers developed a mathematical model to estimate the impact of more broadly distributing naloxone among opioid drug users and their acquaintances. Led by Dr. Phillip Coffin, director of Substance Use Research at the San Francisco Department of Public Health, and Dr. Sean Sullivan, director of the Pharmaceutical Outcomes Research and Policy Program at the University of Washington, the researchers found that if naloxone were available to 20% of a million heroin users, some 9,000 overdose deaths would be prevented over the users' lifetimes.

In the basic research model, one life would be saved for every 164 naloxone kits handed out. But using more optimistic assumptions, naloxone could prevent as many as 43,000 overdose deaths, saving one life for every 36 kits distributed.

Providing widespread naloxone distribution would cost about $400 for every year of life saved, a figure significantly below the customary $50,000 cut-off for medical interventions. That's also cheaper than most accepted prevention programs in medicine, such as checking blood pressure or smoking cessation.

"Naloxone is a highly cost-effective way to prevent overdose deaths," said Dr. Coffin. "And, as a researcher at the Department of Public Health, my priority is maximizing our resources to help improve the health of the community."

Naloxone has proven very effective in San Francisco, with heroin overdose deaths declining from 155 in 1995 to 10 in 2010. The opioid antagonist has been distributed there since the mid-1990s, and with the support of the public health department since 2004. But overdose deaths for opioid pain medications (oxycodone, hydrocone, methadone) remain high, with 121 reported in the city in 2010. Efforts are underway in the city to expand access to naloxone for patients receiving prescription opioids as well. This study is the latest to suggest that doing so will save lives, and do so cost-effectively.

This work by StoptheDrugWar.org is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International

Comments

Ideas for legal opiate regulation

Maybe the best possible policy would be to go so far as to prescribe it on the side with every prescription of an opiate. An idea for when we legalize all opiates for "recreational" purposes, is that you would have to prove that you had a certain amount of naloxone, and that it wasn't expired, in order to make your purchase of opiates. If you didn't, you'd have to buy more naloxone (or maybe the taxpayer could cover it in order to avoid an underground market in opiates, i'm undecided about that), but you'd have to have naloxone and have been trained on how to use it (preferably a course that lasts an hour or a couple of hours, or even less), to be allowed to buy the opiates. In the course they could also cover topics such as a buddy system, not mixing with alcohol (btw, if you a person seems drunk they wouldn't be allowed to buy) or other depressants (or what other drugs in general not to mix with), understanding of doses and tolerance changes, and making sure you take out the needle and not leave it hanging inside your body, as i've heard that's dangerous. I'm no expert, but as far as i understand there are a few main points for using opiates that can go a very long way in saving lives, if not completely prevent the possibility of death (or at least of most deaths). And you'd want the course to teach all that but be fast enough so that people could get their licenses and we could avoid an underground market.

In reply to Ideas for legal opiate regulation by TrebleBass (not verified)

Makes Sense

You could also cover the basics of what we know about breaking free of addiction in the class. Whatever you teach, do it in a way that leaves the students feeling good about attending classes and in a place where other free classes are available, including Freedom from Addiction, Nonviolent Conflict Resolution, and Compassionate Communication.

Been there

This is basically the same as another drug that came out a couple years ago for opiate addiction called Suboxone. What they don`t tell everyone is that these "blockers" are even harder to get off of because they are more addicting than the opiate drug and the cost is almost 10 times the cost. If we want to stop opiate drug abuse and over dose then we need to crack down on the many many doctors that write scripts to anyone with the money to pay. Sooner or later it will be realized that instead of poking the snake with a stick, it is better to just cut off it`s head.

In reply to Been there by BamaDan (not verified)

It's not the same thing

Suboxone (or buprenorhpine) is for treating addiction by emulating the effects of the drug. It effectively does the same thing as the opiates themselves; in fact, it is an opiate. Similarly to methadone, it gets you high just like heroin. The only difference is it is not used to get you high (but it can, in pretty much exactly the same way as heroin). It is taken mostly orally so it is slow acting and more subtle, and it's effects are not found as pleasurable as heroin's for most people, but it does essentially the same thing, and doctors use doses low enough to take away a patient's opiate withdrawal, but does not get them significantly high. They might as well use oral heroin to achieve the same thing (or even iv heroin, and in some countries they do). Its a stupid thing to do in my opinion. The only reason these drugs are used is because of the stupid idea that "well, at least the patients not on heroin anymore" (but he's on a different drug that does the same thing!!!!!). In fact, as you said, some people find actually easier to get off heroin itself than to get off this stuff. Anyway, naloxone is the opposite, it takes away the effects of heroin. Which basically means, you can get high on heroin (with the intention of enjoying it) and if you happen to have taken too high a dose, you can take naloxone to get sober immediately (if you're still conscious enough to take it yourself), or someone else can administer it to you while you're unconscious to bring you back. It's not about treating addiction, it's about saving lives by reversing overdoses.

Add new comment