Teachers Suspended for Showing Flex Your Rights Video

You can read my thoughts on the matter at the Flex Your Rights blog.

As the debate over marijuana legalization rages on and U.S. drug policy draws more public scrutiny than ever before, the arrests and injustices just keep adding up. We can debate the law until we're blue in the face, and we should, but it's equally essential that every American understand the terms of engagement in a battle that catches peaceful people in its crossfire each and every day.

It is because so few of us truly understand our basic rights that police are able to trample them so routinely. But it's also the haunting thought of that knock at the door, and the uncertainty of how to respond, that prevents so many among us from ever coming out of the closet and lending their voices to the debate. Fear and intimidation are the vital instruments without which the war on drugs would have been banished to the bowels of history long ago.

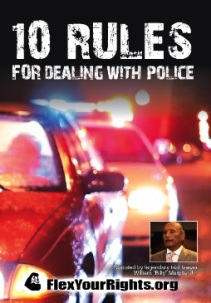

If you haven't yet seen the new Flex Your Rights video 10 Rules for Dealing with Police, please take this opportunity to do so, and please share it with the people you care about. It won't end the drug war, but it might help you get a better night's sleep. And you deserve that.

Here's an Arizona case that illustrates why you should never give police consent to search your vehicle:

The state appellate court has overturned the cocaine-transportation conviction of a Canadian man passing through Flagstaff after ruling the search of his vehicle was illegal.

The reason: The Arizona Department of Public Safety officer who stopped Alvin J. Sweeney, 53, didn't have reasonable suspicion to search his vehicle. [AZDailySun.com]

|

|

|

|

|

As long as the public remains largely ignorant about 4th Amendment rights, police will continue to rely on coercive tactics that treat people as guilty until proven innocent:

Dallas police began a new initiative today to combat drugs. Citywide, officers are headed to suspected drug houses to "knock and talk" with the occupants.

The technique involves knocking on the door of a suspected drug house and trying to talk the people inside into inviting officers in to search without a warrant. Police can enter without a search warrant if they see illegal activity happening.

Dallas police have long used the technique, but its use will be widened during the next few months to include more officers and more areas within the city. [Dallas Morning News]

If this sounds to anyone like a program that only affects drug offenders, it's not. Police tactics like these are always framed as an effort to "get weapons and drugs off the street," but they are so much more than that. By definition, the people targeted under such policies are innocent citizens against whom police have no actionable evidence of criminal activity. After all, when police have credible facts indicating that drug crimes are taking place at a specific location, they may obtain a search warrant and enter lawfully.

The "knock and talk" approach is used exclusively to enter private residences in the absence of probable cause. Vague and unfounded suspicions, or even prejudices, could ultimately determine which locations are singled out for investigation. In the process, innocent people living in high-crime neighborhoods are placed at great risk of arrest in the event that a guest, neighbor or former tenant left something illegal on their property.

As misguided as these tactics are, there is one simple option available to concerned citizens who don't want police digging through their drawers: just don’t let them in. Unless you give them permission to enter, police need a warrant to search your home. You may simply decline the search and tell the officers that you'll gladly cooperate if they return with a warrant. If that makes you uncomfortable, another option is not to answer the door at all, which also reduces the likelihood of police claiming that they saw or smelled something illegal when you opened the door for them.

The bottom line is that invasive "knock and talk" programs don't work if everyone knows their rights, which is why the D.C. police simply canceled theirs after we started doing this:

Anyone in Dallas who's concerned about the new policy should consider organizing a similar effort.

Lesson #1: Never, ever, ever, ever, agree to a search. If youâre guilty, youâre helping them catch you. If youâre innocent, youâre wasting your time, youâre taking a chance since they arenât required to fix anything they break, youâre leaving yourself open for being charged for something you didnât know about that fell out of a friendâs pocket, and youâve got the possibility that a couple of morons will think your coconut candy is crack and throw you in jail for a week.