Phillip S. Smith, Writer Editor

Howard Campbell's "Drug War Zone" couldn't be more timely. Ciudad Juárez, just across the Rio Grande from El Paso, is awash in blood as the competing Juárez and Sinaloa cartels wage a deadly war over who will control the city's lucrative drug trafficking franchise. More than 2,000 people have been killed in Juárez this year in the drug wars, making the early days of Juárez Cartel dominance, when the annual narco-death toll was around 200 a year, seem downright bucolic by comparison.

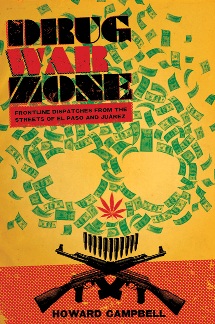

We've all seen the horrific headlines; we've all seen the grim and garish displays of exemplary violence; we've read the statistics about the immense size of the illegal drug business in Mexico and the insatiable appetites of drug consumers in El Norte ("the north," e.g. the US). What we haven't had -- up until now -- is a portrayal of the El Paso-Juárez drug trade and drug culture that gets beneath the headlines, the politicians' platitudes, and law enforcement's self-justifying pronouncements. With "Drug War Zone," Campbell provides just that.

He's the right guy in the right place at the right time. A professor of sociology and anthropology at the University of Texas-El Paso who has two decades in the area, Campbell is able to do his fieldwork when he walks out his front door and has been able to develop relationships with all sorts of people involved in the drug trade and its repression, from low-level street dealers in Juárez to middle class dabblers in dealing in El Paso, from El Paso barrio boys to Mexican smugglers, from journalists to Juárez cops, from relatives of cartel victims to highly-placed US drug fight bureaucrats.

Using an extended interview format, Campbell lets his informants paint a detailed picture of the social realities of the El Paso-Juárez "drug war zone." The overall portrait that emerges is of a desert metropolis (about a half million people on the US side, a million and a half across the river), distant both geographically and culturally from either Washington or Mexico City, with a long tradition of smuggling and a dense binational social network where families and relationships span two nations. This intricately imbricated web of social relations and historical factors -- the rise of a US drug culture, NAFTA and globalization -- have given rise to a border narco-culture deeply embedded in the social fabric of both cities.

(One thing that strikes me as I ponder Campbell's work, with its description of binational barrio gangs working for the Juárez Cartel, and narcos working both sides of the border, is how surprising it is that the violence plaguing Mexico has not crossed the border in any measurable degree. It's almost as if the warring factions have an unwritten agreement that the killings stay south of the Rio Grande. I'd wager they don't want to incite even more attention from the gringos.)

Campbell compares the so-called cartels to terrorists like Al Qaeda. With their terroristic violence, their use of both high tech (YouTube postings) and low tech (bodies hanging from bridges, warning banners adorning buildings) communications strategies, their existence as non-state actors acting both in conflict and complicity with various state elements, the comparison holds some water. Ultimately, going to battle against the tens of thousands of people employed by the cartels in the name of an abstraction called "the war on drugs" is likely to be as fruitless and self-defeating as going to battle against Pashtun tribesmen in the name of an abstraction called "the war on terror."

But that doesn't mean US drug war efforts are going to stop, or that the true believers in law enforcement are going to stop believing -- at least most of them. One of the virtues of "Drug War Zone" is that it studies not only the border narco-culture, but also the border policing culture. Again, Campbell lets his informants speak for him, and those interviews are fascinating and informative.

Having seen its result close-up and firsthand, Campbell has been a critic of drug prohibition. He still is, although he doesn't devote a lot of space to it in the book. Perhaps, like (and through) his informants, he lets prohibition speak for itself. The last interview in the book may echo Campbell's sentiments. It's with former Customs and Border Patrol agent Terry Nelson. In the view of his former colleagues, Nelson has gone over to the dark side. He's a member of Law Enforcement Against Prohibition.

If you're interested in the border or drug culture or the drug economy or drug prohibition, you need to read "Drug War Zone." This is a major contribution to the literature.

This work by StoptheDrugWar.org is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International

Comments

Drug War

is wondering when the government is going to start monitoring Doctor`s on prescription writing and Pill usage on there patients...That`s right, it won`t happen. Most of the people who vote for this are on medication...Do I hear Protest...end this f--king epidemic uncle Sam...Control Prescription Drugs..Also my thought of why the Government will not fight this topic is that they are on medication themselves addicted to there medications...And by making celebrity's that die from drugs look like it`s ok , Does not help our kids decide from whats right and whats wrong..

Add new comment