Feature:

Study

Claiming

Methamphetamine

is

Overrunning

Hospital

Emergency

Rooms

Fails

to

Withstand

Scrutiny

1/27/06

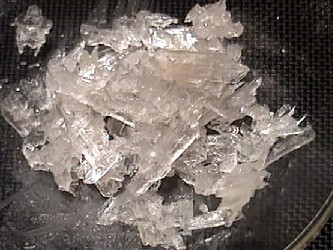

You have to give it to the National Association of Counties (NACo). For the second time in less than a year, the lobbying group for county officials has managed to get the press to bite on methamphetamine studies that purport to show the popular stimulant is wreaking havoc across the land. Last summer, NACo surveyed county sheriffs who screamed long and hard that meth was their worst drug problem. And last week, the group released a study claiming that meth users are overwhelming county hospital emergency rooms and drug treatment facilities.

Those headlines and the stories that accompanied them were based on NACo findings that 73% of hospital ERs surveyed reported an increase in meth-related visits over the past five years and that 47% said meth caused more ER visits than any other drug. On the treatment side, hospitals reported treatment up by 69% over five years, but 63% said they lacked capacity to handle the demand. But the two-part NACo study is a pretty weak reed on which to base such sweeping claims. As methamphetamine hysteria critic Jack Shafer pointed out in Slate, the study's ER sample was 200 hospitals, out of more than 4,000 hospital ERs in the country. The hospitals selected were also skewed heavily toward rural areas (161 of the hospitals were located in counties with less than 50,000 residents) and more meth-prone areas of the country (100 hospitals, exactly half, were in the Upper Midwest, while the entire eastern third of the country accounted for only 19). In that sense, the NACo ER study seems designed to target precisely those areas with the worst meth problems and the fewest resources. "We never said this was a comprehensive survey," said NACo spokesman Joe Dunn. "This was a study of county public hospitals. There are 3,000 of them in the country and we surveyed 200 of them." The fact that the survey was weighted toward rural hospitals was justifiable, too, Dunn said. "Any survey of counties would have a large population of rural hospitals in it." Dunn referred DRCNet to NACo research director Jackie Byers for further discussion of the study's methodology, but Byers is out of the office and unavailable for comment until next week. While Dunn said NACo wasn't portraying the survey as comprehensive, the group used absolutist language in describing the results. The emergency room survey, NACo wrote in its press release, "revealed that there are more meth-related emergency visits than for any other drug and the number of these visits has increased substantially over the last five years." But that's not what the best statistics available say. According to the Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) survey of 121 big city hospital emergency rooms, stimulants rank behind alcohol, alcohol in combination with other drugs, cocaine, marijuana, and heroin in emergency room mentions. According to DAWN's 2003 figures -- the latest available -- cocaine accounted for 20% of drug-related ER visits, marijuana for about 15%, heroin and other opiates for about 12%, and stimulants, including amphetamine and methamphetamine, for only about 7%. And while it could be argued that the DAWN figures suffer from an urban bias and may thus undercount meth-related incidents, the fact remains that most of the nation's hospitals and most of its population are in urban areas. According to the Centers for Disease Control, 58% of all ERs are in urban areas and they account for 82% of all ER visits. Interestingly, the concern over the impact of meth on hospital ERs comes amid evidence that meth use is not spreading in epidemic fashion, but is in fact leveling off. The annual National Survey on Drug Use and Health produced by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Adminstration (SAMHSA), reported that "use of methamphetamine remained unchanged from 2002 to 2004." According to SAMSHA, the number of people who had ever used meth, the number who had used it in the last year, and the number who had used it in the last month had all declined. SAMSHA put the number of monthly meth users at 583,000 in 2004, down from 607,000 the previous year. Those numbers are in line with those from Monitoring the Future, the annual survey of high school students about the drug habits. Among high school seniors, lifetime use of meth has declined steadily since it was first measured in 1997, from 8.2% then to 4.5% in 2004. Meth use in the last month has shown a similar decline, from 1.7% to 0.9%. "The NACo surveys are crap," said Doug McVay, research director for Common Sense for Drug Policy. "There is no data behind them. They surveyed the perceptions of officials at the county level who are responsible for drug treatment and health care services, not the actual numbers. This is an entirely self-serving exercise by NACo whose purpose is to gin up support for additional funding using meth as the reason," he told DRCNet. "The best data we have shows that meth use did increase during the early 1990s, but the rate of increase has been stable for the past five or 10 years. More people are using than a 10 or 15 years ago, but both the growth rate and the number of users seems to be stabilizing." "Governors and law enforcement are all claiming this is an increasing problem, but you have to ask if this is because they want more money for their police forces," said Don McVinney, a methamphetamine researcher and national director of training and education for the Harm Reduction Coalition. "Everyone is using meth to justify more funding. Meth is a hot drug for the media, and it gets media attention. The problem is that these are not disinterested parties, but claims makers. They are saying it's a terrible problem, but you have to look skeptically at the claims, and see what they really mean." McVinney, however, saw little distortion in the second part of NACo's study, where the group identified a need for increased treatment funding. "That is consistent with the data from the federal government -- not only DAWN but drug treatment data as well," he told DRCNet. "That data shows that treatment admissions have gone up steadily since 1993," he said. NACo's Dunn readily admitted the group was seeking to influence funding decisions. "We're looking for the passage of the federal Combat Meth Epidemic Act, which would restrict pseudoephedrine sales, and we're looking for restoration of the Justice Action Grants," he said. "The Bush administration zeroed that out this year, and that was funding that went to multi-agency drug task forces, which are especially critical in fighting meth in rural areas," he told DRCNet. "We're also pushing on the treatment side for an increase in treatment block grants. There is an increasing need for treatment for methamphetamine." Both McVay and McVinney pointed to a problem not emphasized in the study: the lack of access to health care in a country where more than 40 million people are uninsured. "What I found interesting was the subtext. The hospitals were complaining not so much about treating meth-induced problems, but about the fact they were being asked to pay for the treatment," said McVinney. "It was about treating uninsured people. Many meth users end up losing their jobs, so they don't have insurance." "The sad thing is that public health care at the county level is terribly under-funded and it is true that drug treatment is under-funded, too," said McVay. "The NACo study is alarmist propaganda, but the underlying message that the county health care and drug treatment system is in deep trouble is quite true. It's just a shame they are contributing to the hysteria surrounding meth to try to address this broader social issue. When you use unreliable propaganda to basically try to create support for something that's worthwhile -- more funding for health care and drug treatment -- you tend to discredit it." The NACo study fuels the idea that the federal government has somehow not done enough to fight methamphetamine, said McVay. "This also plays into the false notion that the feds have been asleep at the wheel when it comes to methamphetamine," said McVay. "For at least the past 10 years, we have seen escalating federal involvement in the war on meth. There have been tougher laws, more law enforcement, more working groups. If anything, methamphetamine is one of the best examples of the failure of the drug war approach. The drug czar's office has taken some flak from drug warriors about not doing enough, but the notion works for them much better than saying what they've been doing for the past decade didn't work."

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||