Years of effort by harm reductionists, public health authorities, HIV/AIDS researchers and activists, and drug law reformers to undo the more than 20-year-old ban on federal funding for needle exchange programs (NEPs) may come to fruition this year, but there are significant obstacles to overcome. Still, advocates of the reform are cautiously optimistic.

Since 1988, the US government has prevented local and state public health authorities from using federal funds for NEPs, which studies have shown to be effective in reducing HIV infection rates among injection drug users (IDUs) and their sexual partners, promoting public health and safety by taking syringes off the streets, and protecting law enforcement personnel from injuries. NEPS have been endorsed by the World Health Organization, the American Medical Association, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director Thomas Frieden, and former Surgeons General Everett Koop and David Satcher, among many others.

Injection drug use accounts for up to 16% of the 56,000 new HIV infections in the US every year -- or nearly 9,000 people. IDUs represent 20% of the more than 1 million people living with HIV/AIDS in the US and the majority of the 3.2 million Americans living with hepatitis C infection.

Still, those numbers could have been higher. In a 2008 study, the CDC concluded that the incidence of HIV among injection drug users had decreased by 80% in the past 20 years, in part due to needle exchange programs. There are today an estimated 185 NEPs operating in 36 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. But they rely on local or private funds, and many of them are failing to meet demand because of lack of funding. While the CDC says that its public health policy goal is 100% needle exchange, current estimates are that only 3.2% of needles used by drug users in urban areas are exchanged for clean ones.

The federal funding ban was first removed in a July 10 vote of the House Subcommittee on Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies. A week later, the full Appropriations Committee approved the bill after voting down an amendment proposed by US Rep. Chet Edwards (D-TX) that would have reinstated the funding ban.

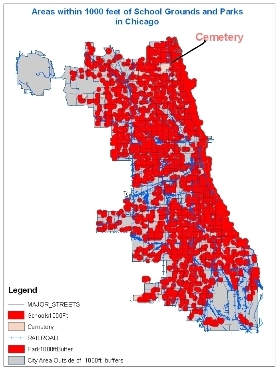

But the Appropriations Committee did approve an amendment dictating that federally funded NEPs could not operate "within 1,000 feet of a public or private day care center, elementary school, vocational school, secondary school, college, junior college, or university, or any public swimming pool, park, playground, video arcade, or youth center, or an event sponsored by any such entity."

A floor amendment by Rep. Mark Souder (R-IN) to reinstate the funding ban also was defeated, clearing the way for repeal of the ban to pass the House. But the thousand-foot language remains in the appropriations bill approved by the House, and it's extremely objectionable to reform advocates. The Senate committee working on the issue did not include ending the funding ban, but reform advocates are pinning their hopes on both ending the ban and killing the thousand-foot restriction on the end-game House-Senate appropriations conference committee.

"The Senate has taken up their version of the bill in committee, but hasn't had a full vote," explained Daniel Raymond, policy director for the Harm Reduction Coalition. "At the committee level, the Senate chose not to take any action on the ban. At this point, there is a conflict between the House and the Senate." HRC is lobbying the Senate to repeal the ban, without the restrictions.

"We commend the full House for recognizing that NEPs are essential, effective tools that work in our fight against HIV and hepatitis transmission," said Kevin Robert Frost, chief executive of the Foundation for AIDS Research. "And while the compromise in the bill isn't perfect, we are hopeful that a final bill will reach President Obama's desk without limitations."

"We urge Congress to recognize both the benefit and cost-savings of syringe exchange programs, and the research that NEPs do not have detrimental impact on communities," said Marjorie Hill of Gay Men's Health Crisis, which has just released yet another study demonstrating NEPs' effectiveness in decreasing the transmission of blood-borne diseases. "For too long, we have allowed ideology to drive public health policy. It is time to remove the federal funds ban for syringe exchange and remove the harmful 1,000 feet restriction," added Hill.

"The House bill, as it stands, still puts ideology before science by limiting how federal funds can be used for NEPs," Frost said. "But we have time to fix the legislation, and I'm hopeful that the full US Congress will realize the importance of allowing local elected and public health officials to make their own decisions about how to address their HIV and hepatitis epidemics."

"I believe that the president, the Senate, and the House all want to do the right thing and they're trying to figure out how to do it," said Bill McColl of AIDS Action. "If they follow their own rhetoric about science- and evidence-based HIV/AIDS prevention policy, then they will remove the thousand-foot restriction," he said.

"The thousand-foot provision is a backdoor means of reinstating the funding ban," McColl continued. "There is almost no urban environment in which it would allow needle exchanges to operate. There are no currently existing needle exchanges that would be able to get federal funding, so it just doesn't make sense to change the policy that way. Drug policy groups have gone and literally shown Congress maps of what would be excluded. They've got letters from mayors and police saying this is not a workable provision. Again, Congress and the president know what the science is."

In addition to eliminating federally-funded needle exchanges in vast swathes of the urban landscape, the thousand-foot rule would have other insidious effects, said McColl. "Having that rule would have undesirable side effects, in that it would separate needle exchange from other public health services. Our AIDS program does testing in areas with lots of drug use -- that's where we need to be testing, and that's where we want the population to have clean syringes. With federal funding available and with the thousand-foot rule, prevention services will be driven away from needle exchanges."

Alice Bell, prevention project coordinator for Prevention Point Pittsburgh, already lives with geographical restrictions. "We have a local regulation that specifies 1,500 feet from schools only, not all the other restrictions in the current language of the federal bill. We have to move our main needle exchange site because the building we're in is being sold, and we're having trouble finding a good place. Any federal restrictions would make it even tougher," she said.

Bell wants the federal funding ban ended, but worries that the thousand-foot rule would put a crimp in her efforts. "We still want it. We need the federal funding. Our program is expanding, but we can't really expand our exchange service because we don't have money for needles. The toughest thing is always getting money for needles. Ending the federal funding ban would make a huge difference to us."

Federal funding becomes even more significant when coupled with economic hard times and budget problems at the state and local level, Bell noted. "We're mostly funded through foundations and private donations, and we've begun getting some state and county money for overdose prevention and HIV prevention, but the needle exchange -- the core of what we do -- is the toughest to get funded."

"The Senate will most likely go along with the House in conference committee," said Drug Policy Alliance director of national affairs Bill Piper. "They will probably take a bunch of appropriations bills and put them in a massive omnibus spending bill. It is far from clear that there will be a ban in what comes out of the Congress."

But the thousand-foot rule has to go, he said. "A lot of groups have been lobbying really hard on the thousand-foot issue," Piper noted. "It would be an effective ban is many cities. Here in DC, for example, the only place you could do a needle exchange program would be down at the docks on the Potomac. The strategy is to convince the conference committee to either take that out or come up with something better."

Advocates are lobbying hard right now, said the Harm Reduction Coalition's Raymond. "Right now, we're doing a push to make sure the Senate is educated about the issue and ask the leadership to get on board with House's action to address the ban," he said. "The House version has the thousand-foot restriction, so we're also making the arguments about why that's not workable and needs to be redone. We've been circulating maps showing its impact to House members who are focused on the issue. This restriction goes far beyond any reasonable desire to balance public health with other interests. When that provision was thrown in at the last minute, its effects hadn't really been thought out," he argued.

"We keep up the work in reaching out to Congress on both House and Senate side," said Raymond, "and we're also asking the White House to show some leadership and urge the Senate to address the federal ban. We don't want this issue to get lost in the shuffle, we're calling on everyone in the community to make our voices heard and reaching out to our elected officials."

It may take awhile to get settled, said Piper. "The entire appropriations process is messed up, and a lot of will depend on if, when, and how the Senate deals with health care," he explained. "Supposedly, they will get the appropriations bills done by the end of October, but I think that's a fantasy. Last year, they didn't even do this year's appropriations bills until March."

Still, AIDS Action's McColl maintains a positive outlook. "I think the members who will be called on to vote on this understand the issues," he said. "I have a pretty good feeling about this. I'm hopeful this is the year."

This work by StoptheDrugWar.org is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International

Add new comment