Latest

Latest News

Latest News

Latest News

Latest News

Latest News

Blog

Take this drug tax and...

|

|

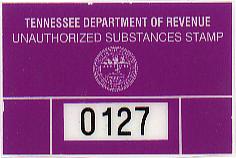

| click on image to enlarge in separate window |

"The pot that I am being taxed on was found in containers on my property which I couldn't see from my house. I had less than an ounce in my house. You would think if I were going to keep that much valuable pot just laying in the weeds where anyone could help themselves to it, I would have at least put no trespassing signs on my place, which I didn't.""You should see the list of damage they did to my things," he added.

|

|

|

|

Chronicle

Editorial: Does Anything Go in the Drug War?

Drug taxes, loss of aid, mandatory minimums, pain prosecutions, no-knock drug raids, fumigation, forfeiture, death penalties -- If anything goes in the drug war, then where does it end?

Latest News

Chronicle

Weekly: This Week in History

Events and quotes of note from this week's drug policy events of years past.

Chronicle

Feature: Battlelines Forming Over 2008 Oregon Medical Marijuana Ballot Issues

Oregon's medical marijuana program is 10 years old and rolling along, but it looks like it will be contested terrain next year, with one initiative already filed to repeal it and others to expand it.

Chronicle

Law Enforcement: This Week's Corrupt Cops Stories

Another week's worth of law enforcement officers done in by the temptations created by drug prohibition, including a sheriff headed for prison for turning a blind eye, a prosecutor whose coke habit got him in trouble, a greedy Boston cop, and a pair of pill-peddling policemen.

Chronicle

Death Penalty: Two More Drug Offenders Executed in Iran, Six Sentenced to Die in Vietnam

The resort to the death penalty for drug offenders continues in Southeast Asia and the Middle East, with two executed in Iran last week and six sentenced to death in Vietnam.

Chronicle

Drug Penalties: Tennessee Appeals Court Finds Drug Tax Unconstitutional

The Tennessee Court of Appeals has thrown out the state's illicit drug tax. The state will appeal, and plans to continue assessing the tax in the meanwhile.

Chronicle

Law Enforcement: Asset Forfeiture Funds Spent on Banquets, Balls, and Balloons in Atlanta

Georgia's Fulton County (Atlanta) district attorney has some odd ideas about how asset forfeiture funds should be spent, an audit of his books has found.

Chronicle

Prohibition: Terror Groups Profit From Drugs, DEA Says -- Missing Forest For Trees

A high-level DEA official has again linked the illegal drug trade to the funding of terrorist organizations, but failed to note the role of drug prohibition.

Chronicle

Latin America: Colombian Vice-President Says Aerial Eradication is Failing

The Colombian government has offered its strongest criticism yet of US-backed aerial spraying of coca crops, saying it has been a failure.

Chronicle

Ghosts of Prohibition: Women's Christian Temperance Union Holds Indianapolis Convention

The Women's Christian Temperance Union lives -- barely -- and is meeting this week in Indianapolis to continue the battle against demon run and its contemporary counterparts.

Pagination

- First page

- Previous page

- …

- 1060

- 1061

- 1062

- 1063

- 1064

- …

- Next page

- Last page