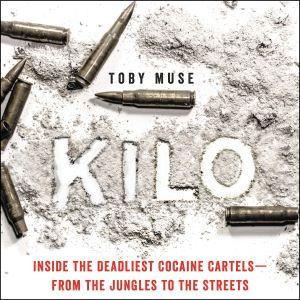

Kilo: Inside the Deadliest Cocaine Cartels -- From the Jungle to the Streets, by Toby Muse (2020, William Morrow, 303 pp., $28.99 HB)

It's also -- and not coincidentally -- been one of the most violent countries on the planet. A decades-long civil war between the leftist militants of the FARC and the Colombian state left hundreds of thousands dead and millions displaced. And after coca and cocaine took hold beginning in the 1980s, that civil war morphed into a vicious, multi-sided conflict featuring not only more leftist guerillas of various stripes and Colombian military and police forces aided and abetted by the US, but also various rightist paramilitary forces controlled by drug lords and conservative wealthy landowners working in collusion with security forces.

With Kilo, Bogotá-based journalist Toby Muse dives deep inside Colombia's coca and cocaine trade to provide unparalleled reporting both on the industry and on the dance of death it provokes again and again and again. He starts at the beginning: in the coca fields of a Catatumbo province, near the Venezuelan border. There, refugees from the economic implosion across the line now form the majority of raspachines, the farm hands whose job it is to strip the bushy plants of their coca-laden leaves. At the end of each harvest day, they tote large bags filled with the day's haul to the farm scale to be weighed and paid. They might get $8 a day.

In simple labs -- a wooden shack or maybe four poles and a tarp -- that dot the jungly countryside -- those humble leaves are pulverized and steeped in a chemical brew to create coca paste, one step away from the white powder, cocaine hydrochloride. A ton of leaves is transformed into a kilo and a half of paste, which the farmer can sell for about $400. That used to be good money, but the price has held steady for 20 years, there's more coca than ever, and costs have gone up.

But while the introduction of coca as a cash crop initially brought boom times, the smell of all the cash being generated inevitably attracted the attention of the armed groups, those strange hybrid revolutionary drug traffickers and rightist narco-militias. And that meant fighting and disappearances and massacres as the men with the guns fought to control the lucrative trade. Where coca comes, death follows, Muse writes.

Muse follows the kilo, now processed into cocaine, to the local market town, a Wild West sort of place where traffickers meet farmers, farmers get paid, and the local prostitutes -- again, now mostly Venezuelan -- get lots of business. He interviews all sorts of people involved in the trade or affected by it, from the $12 an hour sex workers to the drunken, just paid farmers and raspachines and the business hustlers who flock to the town to peddle flat screen TVs and the urban traffickers who come out to the sticks to pick up their cocaine.

And then it's on to Medellin, famed as the home of OG drug lord Pablo Escobar, and now a bustling, modern metropolis where cocaine still fuels the economy but where the drug barons are no longer flashy rural rubes but quiet men in suits, "the Invisibles," as they're now known. They may be lower profile, but they're still ruthless killers who hire poor, ambitious local kids, known as sicarios, to do the actual killing. Muse wins the confidence of a mid-level trafficker, a former policeman who learned the trade from the other side and now applies his knowledge to run an international cocaine network.

And he parties with the narcos at Medellin night clubs, techno music blasting, guests wasted on whiskey and cocaine and 2-CB ("pink cocaine," like cocaine with a psychedelic tinge, an elite party drug that costs $30 a gram while cocaine goes for $3). This glamorous life is what it's all about, what makes the constant fear or death or imprisonment worth it:

"The clubs feel like the center of this business of dreams. Cocaine has all the nervous energy of a casino where everyone keeps winning money, sex is everywhere, and at any moment, someone might step up and put a bullet in your head. This is the deal in cocaine and people are happy to take it."

Nobody expects to last too long in the trade, but they live the high life while they can. Muse's drug trafficker, Alex, doesn't make it to the end of the book, gunned down by somebody else's sicario. But before he is killed, that titular kilo makes its way out of the country and into the eager noses of London or Los Angeles.

Muse's descriptions of life in the cocaine business are vivid and detailed; his atmospherics evoke the tension of lives outside the law, where no one is to be trusted, and brutal death can come in an instant. A young sicario whom he interviews over a period of months, ages before our eyes, killing for his bosses, afraid of being killed in turn, and numbing himself in between hits with whiskey and cocaine. He wants out, but there looks to be no exit.

As a good journalist, Muse also interviews the drug law enforcers, the cops who bust mules at the Bogotá airport, the drug dog handlers running the aisles of massive export warehouses, the naval officers who hunt down the narco-subs. And it is only here, where the futility of their Sisyphean task is evident, that any critique of drug prohibition is articulated:

"">No one knows how widespread corruption is in the airports and ports. Police officers admit it's a huge problem, but only in private, off the record. That's the hypocrisy of the drug war. In formal interviews, officers point out how well they're doing, the positive results. And as soon as the interview is over, and the recorder stops, they sit back and tell you what's really happening. They tell you of the constant problem of corruption, how the war is unwinnable, and how the only solution is legalization. In private, to state that the war on cocaine can be won would make you look like an idiot. To admit the war is unwinnable in public is to end a career."

That's as close as Muse gets to any policy prescriptions. Still, Kilo digs as deep into the trade as anyone ever has, and he has the journalistic chops to make a bracing, informative, and very disturbing read. This may be as close to the Colombian cocaine business as you want to get.

This work by StoptheDrugWar.org is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International

Add new comment