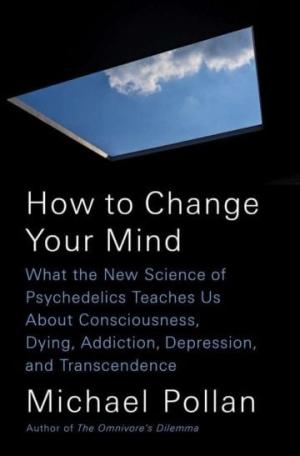

Can psychedelic drugs improve our lives? Michael Pollan thinks so, and he makes a pretty persuasive case in his latest book, How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence.

The subject is something of a departure for Pollan, who has risen to prominence as the consummate foodie, authoring such well-known tomes as The Omnivore's Dilemma, Food Rules, and In Defense of Food. But it's not entirely surprising: In his 2001 The Botany of Desire, Pollan delved into the world psychoactive substance to examine the mutually beneficial relationship between humans and marijuana. (He also described our relationship with apples, tulips, and potatoes.)

In his current effort, Pollan dives into the science of psychedelics, going deep into brain chemistry and the actual mechanisms by which these drugs alter consciousness. Basically, the science suggests, psychedelics damp down the brain's default mode network, the cerebral mechanism that allows us to maintain normal consciousness. When the default mode network is weakened, new neural pathways open up, brain parts that don’t usually communicate with each other start talking, and the going gets weird.

And that opens the door not only for trippy imagery, but also for spiritual epiphanies or, less grandly, coming to terms with oneself and one’s issues. As Pollan reviews the current research taking place in this psychedelic revival, he encounters terminal cancer patients whose closely guided trips help them grapple with their own mortality, spiritual seekers finding enlightenment, and drug users who find themselves able to break noxious addictions.

He also tries psychedelics himself -- something he hadn't done before -- taking LSD, magic mushrooms, and toad venom containing DMT. His description of his experiences is vivid and compelling, and he tries his best to express those ineffable "truths" the psychedelic experience offers. Describing the subjective reality of an acid trip is a difficult feat, and Pollan does better than most.

And speaking of magic mushrooms, who knew that the term was coined by a Time/Life publicist in the 1950s? I didn't. But that was indeed the case as Life editors were putting together the groundbreaking tale of Gordon Wasson's experience eating psilocybe cubensis with Mexican shaman Maria Sabina.

Pollan's book is full of such delicious little tidbits of psychedelic lore and history, including an account of the Stoned Ape hypothesis, favored by some mycophiles, which argues that hominids ingesting magic mushrooms led to the development of human consciousness.

But it also tells the tale of psychedelics as never before, revealing a "secret history" of lost research on psychedelics in the 1950s and 1960s, where thousands of subjects ingested them in more than a thousand scientific experiments. Some of the results were impressive -- LSD appeared to help curb alcoholism, as well as helping people come to terms with mental disorders or terminal illnesses -- but that body of research was largely forgotten as the federal government and scientific establishment led a severe crackdown once Tim Leary and the hippies got ahold of acid.

Naturally, Leary remains the central figure of the 1960s psychedelic scene -- and a highly contentious one -- but one of Pollan’s biggest contributions is showing how psychedelics were busily leaking out of the lab and into the culture at large in ways that had nothing to do with Leary. Hollywood actors and other elites were taking LSD in therapeutic sessions, spreading the word and participating in group sessions that in some cases seemed more like acid parties than therapy sessions.

Still, once Leary shed his researcher's objectivity to become a messianic acid missionary with his slogan of "tune in, turn on, and drop out," and undertook a mission to cure not sick people but the culture itself, it was game over for the first wave of psychedelic research:

"The fact that by their very nature or the way that first generation of researchers happened to construct the experience, psychedelics introduced something deeply subversive to the West that the various establishments had little choice but to repulse. LSD truly was an acid, dissolving almost everything with which in came into contact, beginning with the hierarchies of the mind (the superego, ego, and unconscious) and going from there to society’s various structures of authority and then to lines of every imaginable kind, between patient and therapist, research and recreation, sickness and health, self and other, subject and object, the spiritual and the material. If all such lines are manifestations of the Apollonian strain in Western civilization, the impulse that erects distinctions, dualities, and hierarchies, and defends them, the psychedelics represented the ungovernable Dionysian force that blithely washes all those lines away."

For the past half-century, psychedelics have been making a slow, but now rapidly accelerating recovery from the repression sparked by Leary's proselytizing and the specter of a psychedelicized America. Again, Pollan shines with his explication of the mind-blowing research taking place and the possibilities being opened up. If there was any question that psychedelics are enjoying a scientific and medical renaissance, Pollan puts that to bed.

Yet, in awe of the power of psychedelics, Pollan stops short of calling for their legalization. Instead, he seems to want every trip to be guided, every journey to have a destination. Has he been captured by the very scientists and researchers whose stories he tells? He writes about the spiritual and the psychological, religion and science, and "shamans in white lab coats," but he doesn't want to talk about recreational use of the drugs.

But the psychedelics are here, and they are being used just for fun. The molecule is in our midst and the fungus is among us. Neither is going away nor are they staying in the lab.

How to Change Your Mind is a major addition to the literature on psychedelics. Reading it will blow your mind. Do it now.

This work by StoptheDrugWar.org is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International

Add new comment