Feature:

Dramatic

Death

Toll

in

Sao

Paulo

as

Drug

Gangs,

Police

Clash

5/19/06

More than 160 people, including at least 75 police and prison guards, have been killed in a series of prison uprisings and urban attacks led by drug trafficking organizations in South America's largest city. In a wave of violence that began last weekend, partisans of the First Capital Command (PCC), Sao Paulo's leading gang, rebelled in at least 80 of the province's more than 115 prisons, while their masked comrades on the outside attacked police posts, bars, banks, and burned at least 59 buses, according to figures current as of Thursday.

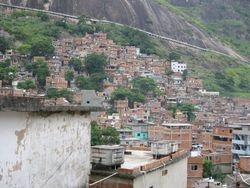

Paulo de Mesquita Neto, of the Sao Paulo Institute Against Violence, told reporters Wednesday a "strategy of retaliation" was taking root. "Initially the police seemed to have had some success and had the support of the population. In the last few hours, however, they seem to have gone looking for revenge... If the police force starts going down this path it will be showing it is unable to cope." According to Brazilian press accounts, the uprising began when PCC gang leaders who run their enterprise from prison cells learned they and more than 700 of their imprisoned comrades were about to be transferred hundreds of miles away to maximum security prisons in an effort to break their hold over the command's operations. Using cell phones -- illegal in prison but widely available nonetheless -- PCC leaders ordered the wave of attacks. By last weekend, gang members were shooting up police cars, attacking police stations with hand grenades, and going after police in their homes and after work hangouts. On Sunday, they began burning buses. By Monday, thousands of bus drivers refused to work, leaving nearly three million people dependent on public transport scrambling to find a way to get to work or school. The normally teeming city center was a virtual ghost town Monday afternoon. By Tuesday, the buses were running again, but again many people stayed home and many businesses and offices remained shuttered. Bus driver Gilson Adei told the Associated Press Tuesday police should strike back hard -- an increasingly common sentiment in the shell-shocked city. "It's absurd -- the gang members can do whatever they want? They can just start a war? And why would they attack the transportation, normal people? Next it will be schools," he said. "We should get the military on every corner and kill them." Instead, according to Brazilian press reports, authorities cut a deal with imprisoned PCC leaders to end the violence. The state would promise not to send in brutal "shock teams" to retake the prisons, would not transfer the leaders to distant prisons, and would restore other privileges for imprisoned PCC leaders. In return, PCC leaders reportedly made the phone calls that called off their fighters. But whether the agreement -- widely criticized as caving in to criminals -- will hold in the face of an apparent wave of revenge killings by police remains to be seen. "It was all fucked up. There were no buses running, schools and colleges shut their doors, shops were closed, people were really scared," said Martin Aranguri Soto, a graduate student in political science at the Pontificia Universidade Catolica de Sao Paulo who is studying the history of prisons. "The city came to a halt. It was really weird to see all the people walking home Monday night because the buses weren't running," said Aranguri Soto, who also serves as Drug War Chronicle's Spanish and Portuguese translator. "I rent a room to some prison guards, and they are scared shitless" because of the outbreak of prison riots where guards have been held hostage, he said. The "commands," as the criminal organizations are known, have grown fat off profits from the cocaine trade in a country that is now the world's second leading cocaine consumer, trailing only the United States. Based in the teeming slums known as favelas that are home to millions of Brazilians living in dire poverty, especially in Sao Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, the commands have become a sort of parallel government. In vast urban areas left largely unattended by the Brazilian state, the commands provide not only drugs, but law and order, in essence replacing a state that lacks the will or the resources to serve the needs of its poorer citizens. A peculiarly Brazilian mutation, the commands have roots going back to the military dictatorship of the 1960s and 1970s, when common criminals and political prisoners mingled in the dictatorship's prisons. By 1979, the first of the commands, the Green Command, was born under the motto of "Peace, Justice, and Liberty." But while the commands originally had a political tint, vestiges of which remains in vague allusions of support for Western bogeymen like the Taliban, they grew rich, and increasingly well-armed, from the drug trade. Now, for most Brazilians, the commands have a political role, but only as "the party of crime." The PCC grew out of a split in the Green Command, which was based mainly in Rio, and now dominates Sao Paulo's criminal underworld with thousands of armed men and hundreds of thousands of indirect employees. The commands' wealth and largesse -- they organize cultural events like the "funk balls" that draw thousands of partiers into the favelas, as well as donating goods and services and providing security for favelas -- provides them with a large social base in the informal hillside communities. "The commands gained influence in the favelas in the 1980s and early 1990s, when the black market drug trade became their main activity and also became almost the sole employment opportunity for favela inhabitants," said retired Sao Paulo Judge Maria Lucia Karam. "Their influence in the favelas says much about the Brazilian state," she told DRCNet. "It reveals the state's lack of concern for poor people. The only way poor teens, young adults, or even favela children can find to be recognized and respected is to work in the black market drug trade. They can have a big gun and stylish clothes. They know they will probably be killed or go to prison, but they don't mind because they believe it's better to lead such a dangerous life than to live under all kinds of oppression." "The commands are very busy and very angry," said Karam of the wave of attacks and rebellions. "I don't approve of violence against people, but unfortunately this is the only way Brazilian prisoners and their friends find to react to the oppression and the inhumane conditions of prisons, especially the maximum security ones. Those prisons are sadistic places, and those treated with sadism tend to also react with sadism." While a rising chorus of angry Brazilian politicians is calling for new, more severe measures to fight the commands, that is no solution, Karam said. "Violence in our drug markets is a result of illegality," said Karam. "The solution is to reform the UN conventions and the national laws to legalize the production, sale, and consumption of all drugs." But given Brazil's problems, that isn't enough, she said. "We have to radically change the way the state responds. We cannot confront the violence of the commands with state violence. We have to respect the rights of all Brazilians, including prisoners. Instead of proposing more severe laws, as almost everyone now wants in Brazil, we have to figure out how to reduce the intervention of the criminal justice system. And we have to recognize that all human beings deserve equal respect. We cannot demand respect and peace if we don't really respect all our people." "Everybody is outraged and almost rabid, they want security," said Aranguri Soto. "But the PCC's fight is against the state, not civilians. There were only four civilians killed in the crossfire. I can condemn the means used by the PCC, but I refuse to be afraid because the state gains when the citizens are afraid. All governments are based on fear, and when the state says 'Don't be afraid, we will protect you,' that means it is going to extend its powers," he argued. "One of my class mates was on one of the buses that were attacked," Aranguri Soto continued. "Do you know what she said? She said they were really polite. They only asked passengers to hand over their cell phones and asked them to cooperate and said they were going to burn the bus. So the people got off, and they burned the bus." While event-driven Brazilian legislators are pushing to pass tough anti-gang legislation this week, the administration of Brazilian President "Lula" da Silva is appealing for more considered deliberations. Lawmakers "should not succumb to the temptation of panic legislation," Justice Minister Marcio Thomaz Bastos told Agencia Estado, the official Brazilian news agency. Brazil is reaping the results of low spending on social programs since the 1960s, he said. "Either we give these youths hope, or organized crime will." This week's violent outburst was shocking, but no surprise, said penal scholar Aranguri Soto. "I can't say this wasn't predictable, because it was," he said. "The government of Sao Paulo has been building prisons like crazy, and with more than 100,000 prisoners, it has almost a third of the entire Brazilian prison population. Those prisons are filthy, overcrowded, and dangerous for prisoners and guards alike. It may be over now, but you can write this down: It will happen again, and next time it will be all of Sao Paulo's prisons. The state has been incubating its own cancer."

|