Feature:

Drug

Possession

for

Personal

Use

is

Not

a

Crime,

Argentine

Court

Rules

2/16/06

In a decision that could bring the question of whether drug possession is legal or not in Argentina to that country's Supreme Court, a judge in the in the province of Buenos Aires has ruled that a tough provincial law penalizing drug possession violates the South American republic's constitution. Penalizing drug possession for personal use is barred under the constitution's privacy provisions, Court of Guarantees Judge Luis Estaban Nitti ruled in the last week of January. A second provincial judge has since followed in Nitti's footsteps.

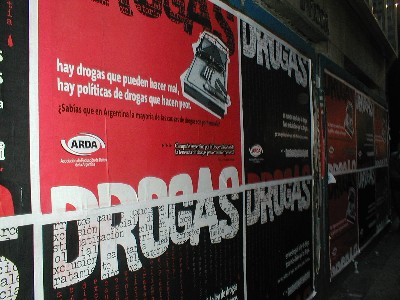

"Up until last year, drug crimes were punished only under federal law," said Silvia Inchaurraga of the Argentine Harm Reduction Network (ARDA), which has been a leading force pushing for drug law reform in the country. "But in Buenos Aires province, they decided to create their own provincial drug law. ARDA demonstrated against this law last year, saying it would only increase the repressive power of the state and lead to corruption in the police force, which is already known to be corrupt. We also said that this law would only broaden the persecution of drug users." The provincial Supreme Court statistics suggest that Inchaurraga and ARDA were correct. In its review of Buenos Aires province drug arrests, the court found that 84% were for simple drug possession and 86% were busted for marijuana. "This evidence shows that it's not true that the law is helping police catch the big drug dealers, just punishing more drug users," she said. Defense attorneys in Buenos Aires province moved to challenge the law, despite believing that their efforts would be fruitless in the provincial courts. "I now come forward to ask that the law is declared unconstitutional, particularly the section that reads 'the penalty will be from one month to two years in prison when the small quantity and the rest of the circumstances suggest unequivocally that the possession is for personal use," said Dolores district court assistant public defender Veronica Olindi Huespi in her motion to the court seeking to overturn the law. Much to her surprise, Judge Nitti agreed. "The scourge of drugs in our society must be combated with all our strength and means, but without resorting to terror or easy solutions that point in the direction of the person who possesses drugs for personal use, while not focusing on the drug traffic, a sector where unscrupulous people are filling their pockets," he noted in the case of a youth arrested for possessing eight grams of marijuana and rolling papers at a concert. "By punishing simple drug possession for personal use, the state only adds to the problem of drug addicts or, in the case of recreational drug users, by criminalizing them and inserting them into the penal system." "We tried this believing that they would tell us no and that we would go through successive stages of appeal until arriving at the Supreme Court of the Nation," Veronica Olindi Huespi, assistant public defender in the judicial district of Dolores, told Pagina 12. Nitti threw out 35 drug possession cases, but allowed cases against five people caught smoking marijuana in public to stand. Those cases were different -- and punishable -- Nitti ruled, because "the person is in public and in that manner is affecting the public health," a portion of the decision that did not sit well with Olindi Huespi.

The issue is not a new one in Argentina. Even during the rightist military dictatorships on the 1960s, Argentine jurists upheld the right of people to use drugs, but that changed with the rise to power of Jose "The Warlock" Lopez Rega, the Rasputin-like behind-the-scenes advisor to then President Isabel Peron, who pushed through a law that not only recriminalized drug possession, but cast it as an offense against national security. With the fall of the post-Peron military government after the Falklands debacle, Argentine jurists returned to their earlier reasoning, and in its 1986 Bazterrica decision, the Supreme Court reaffirmed that the constitution's privacy provision protected drug possession for personal use from the power of the state. But that decision was overturned a few years later by a new Supreme Court packed with judges appointed by then President Carlos Menem, and there matters stand pending resolution of the current case. While discontent over arresting people for simple drug possession has been simmering in the Argentine judiciary and some federal judges have simply placed drug possession cases on hold, the case from Buenos Aires province appears to be the first destined to provide a rehearing of the issue at the Supreme Court. The judicial challenge to Argentina's laws against drug possession runs parallel to an effort in the national legislature to undo them. As DRCNet reported during last fall's Buenos Aires conference on hemispheric drug reform, two Argentina legislators working with ARDA, Deputy Eduardo Garcia and Sen. Diana Conti, introduced bills that would decriminalize -- or in the favored Argentine terminology, "depenalize" -- drug possession for personal use. "These are good bills, and ARDA was involved in this, but we don't think we have the votes to pass them," said Inchaurraga. "We think there is a better chance the Supreme Court will declare the law unconstitutional. There are now lots of judges saying they cannot punish drug possessors because it was for personal use, that they think it is crazy to punish people for this, and we think we have some friendly judges on the Supreme Court as well. If we can get a case to the Supreme Court, we think we could get a ruling this year that the law is unconstitutional." The ruling won support from prominent judicial and criminal justice figures in Argentina and neighboring countries. "As a defense attorney, I have argued the same," said Stella Maris Martinez, whom President Kirchner has nominated to be head public defender for the country, in an interview with the Buenos Aires newspaper El Pais. "It is unconstitutional to repress the possession of small quantities of drugs for personal use because it does not affect the public health. The decision of the judge in Dolores is very good. Now we are ready to bring a case to the Supreme Court." "The law is reactionary," said La Plata federal court judge Leopoldo Schiffrin in an interview with Pagina 12. Federal judges don't like it and have acted to undercut it, he said. "In general, federal judges have shown themselves very reluctant to pursue proceedings in cases of possession for personal use."

Since Nitti ruled, another provincial court judge, Daniel Viggiano in Lomas de Zamora, has followed his lead. In a decision announced February 6, Viggiano declared the drug possession law unconstitutional, saying that personal drug use did not affect the public health. The Argentine constitution's Article 19 guarantees "the right to privacy" and "defines a sphere of individual liberty that excludes the intervention of the state," he ruled. At least one leading Brazilian jurist looked on enviously. The Argentine provincial court decisions build on the "remarkable" earlier Supreme Court decisions asserting the privacy right under the Argentine constitution, said retired Court of Rio de Janeiro Judge Luisa Maria Karam. "The right to privacy protects the individual option for using drugs, or possessing them for personal consumption, or doing any other thing that does not affect directly and concretely the rights of others," she told DRCNet. "This right to privacy is an expression of the principle of legality that submits the exercise of state powers to the rule of law and guarantees individual freedom as a general rule, situating prohibitions or restrictions as exceptions that can only be established in order to guarantee the free exercise of rights of others." The rulings are also justified under the "principle of hurtfulness," said Karam. "The individual option for using drugs, or possessing them for personal consumption, or doing any other private behavior, is also protected by the so-called principle of the hurtfulness of the prohibited behavior, under which criminalization is authorized only if a behavior is able to cause a concrete and significant damage or injury to others." While the Brazilian constitution is not as explicit on the issue of privacy, said Karam, "a similar case could and should be made under Brazilian law." Some Brazilian judges are already deciding cases along similar lines, she said. In Colombia and Peru, simple drug possession is already decriminalized. Now, a case that could return Argentina to those ranks may make its way to the Supreme Court. If Brazilian jurists and defense attorneys would embrace similarly creative thinking, the same could happen in South America's largest country. In the Western Hemisphere, at least, it appears Latin America is leading the way to fundamental reform of the drug laws.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||