Feature:

States,

Colleges

Block

Financial

Aid

to

Students

with

Drug

Convictions

Even

When

They

Don't

Have

To,

DRCNet-sponsored

Study

Finds

2/10/06

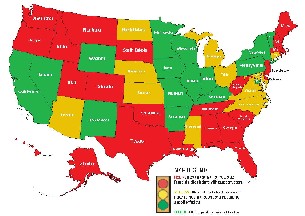

Thousands of college students with drug convictions could be receiving financial aid from their states even though federal law bars them from obtaining federal assistance, a study released this week has found. Only seven states have laws similar to the federal Higher Education Act (HEA) drug provision, the law that bars federal aid, but many others fail to provide state aid to students with drug convictions even though they could do so, according to the report, "Falling Through the Cracks: Loss of State-Based Financial Aid Eligibility for Students Affected by the Federal Higher Education Act Drug Provision," published by the Coalition for Higher Education Act Reform (CHEAR) and its sponsor group, DRCNet.

But even with the Souder fix, students who are ineligible for federal aid but who could receive state financial aid will not do so -- unless administrators, state financial aid agencies, or, in some cases, state legislatures take steps to make it happen. The report found that in 35 states, state law, administrative policies, or institutional whim resulted in students being unable to gain access to state funds that could help them achieve a higher education. In addition to the seven states that legislatively ban aid to drug offenders, 17 others that rely on the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) form for aid-granting decisions effectively bar otherwise eligible students and 11 states leave the decision in the hands of individual schools. That the issue still resonates despite passage of the so-called "Souder fix" was demonstrated by the national press coverage the report generated almost immediately. It was prominently featured in a USA Today story about efforts to reform the HEA drug provision and picked up in an Associated Press story that has run in newspapers across the country. The Chicago Tribune and the Chronicle of Higher Education are both planning pieces, and the report is beginning to show up in college newspapers as well. "As we did work at the federal level, we were shocked to discover that a lot of state agencies and institutions that deal with financial aid are just flat-out confused by the drug provision," said outgoing CHEAR campaign director Chris Mulligan, the report's lead author. "Most states are following the federal lead solely out of administrative convenience, and many state agencies seemed to even be unaware that's what they were doing," he said. "The real story, and the real travesty, is that there are students in lots of states who can get state financial aid, but aren't because of administrative laziness or ignorance," Mulligan said. "Some states or schools just put them in the reject pile if they don't qualify for federal aid because of a drug conviction. Others say they don't have the resources to analyze the data or create a separate form. The end result is a lot of people are wrongfully being denied student aid."

The report makes specific recommendations for change. Some are aimed at state legislatures, others at state executive branches and their financial aid agencies. Yet others target universities and the Department of Education, which administers the federal aid program. According to the report:

Despite partial reform in the last Congress, the issue continues to generate controversy, and activity. Students for Sensible Drug Policy (SSDP), another member of the CHEAR coalition, last week announced it would sue the Dept. of Education to get the state-by-state breakdown -- with the help of Public Citizen, a national nonprofit organization concerned with openness and accountability in government as well as consumer advocacy -- after the department refused to release that information unless the group paid a punitive fee for the privilege. The department argued bizarrely that the information would serve no public policy purpose and that SSDP, a nonprofit organization, could somehow profit financially from the group's stated goal of "ending the war on drugs." That's not the only legal challenge to HEA drug provision. The American Civil Liberties Union Drug Law Reform Project, another coalition member, is preparing a nationwide class-action lawsuit targeting the officials responsible for denying aid to students with drug offenses. The lawsuit will challenge the law on constitutional grounds. In the meantime, CHEAR and DRCNet, while still aiming at outright repeal of the law on Capitol Hill, are now also focusing on ameliorating the damage at the state level. "We want to change financial aid policies in the states while continuing to draw attention to the larger federal issue at the same time," said DRCNet executive director David Borden. "The first step is to get dialogue started," he added, pointing to the report already having generated such a discourse at the University of Virginia in pages of the student paper The Cavalier Daily. As the report notes in its section detailing the laws and policies in each state, Virginia has no state law barring students with drug convictions from obtaining state aid, and policies vary from school to school. The University of Virginia does not grant state aid. But UVA's financial aid director, Yvonne Hubbard, didn't seem to have a strong reason. The university bars students from getting state aid because as a public institution, it wants to align its policies with those of the federal government, she told the Daily. "We have determined here that our institutional money will be processed in the same [manner as] our state and federal money, which is predicated on the FAFSA," Hubbard said. "Ms. Hubbard may be under a misconception when she says the school aligns its aid policies with the federal government because it's a public institution," said Borden. There is no federal law or policy mandating that Virginia or UVA mimic the federal HEA drug provision. They are expected to use a federally-approved need analysis system, but that's a different issue and it does not require them to use the FAFSA in determining state aid and many states don't. Our research found that there are other schools in Virginia that have taken the steps needed to include people with past drug convictions in their state aid programs and that state policy allows for it." "What we want to see is those state agencies, other institutions, and legislators come up with solutions to this problem," said CHEAR's Mulligan. CHEAR and DRCNet are going to have to do it on a limited budget. The campaign does not currently have a targeted grant for it, and staff are being laid off. But despite some belt-tightening at DRCNet, the campaign will continue, said Mulligan. "CHEAR continues to exist, and we hope this will excite people so we can once again hire staff for the project. A lot of people think that with the HEA drug provision being scaled back, there's not a lot to do at this point, but this report shows there is plenty to do," he argued. "We'll be looking at 10 to 15 states where we have allies or see openings to make some progress," said Borden. There is also unfinished business on Capitol Hill, Borden said. "I think the HEA drug provision needs to be repealed outright." The Senate's Health, Education, Welfare & Pensions (HELP) Committee last year approved a further reaching reform than the one ultimately adopted by Congress, but it never received further discussion because education legislation including the Souder change to the drug provision was tacked onto the budget reconciliation bill that was steamrolled through Congress at the 11th hour late last year. "There was no education conference committee, and there was really no budget conference committee except on paper. And the head of that paper committee, Sen. Judd Gregg (R-NH), is the original Senate sponsor of the drug provision and is markedly less sympathetic to repeal than most HELP members are, to say the least," Borden explained. "HELP's version of reform should at least get a fair discussion." The undaunted Borden has bigger plans, too. "Mostly this year we will be looking to expand the effort to other federal laws that single out people with drug convictions, starting with those that bar people from receiving public assistance or being able to live in public housing. It took seven years to get something to finally change on HEA; it's not too early to take on the rest."

|