Feature:

Vancouver

Keeps

Leading

the

Way

on

Drug

Reform,

Despite

Bumps

in

the

Road

12/9/05

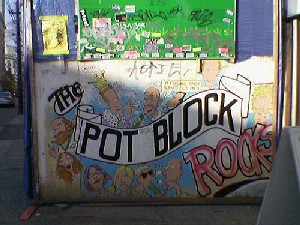

Downtown Vancouver's famous Pot Block is a bit quieter these days with "Prince of Pot" Marc Emery's operations greatly reduced since his indictment on marijuana trafficking charges in the United States for selling seeds, and the glory days of brazen, media-grabbing retail pot sales at Da Kine Café on Commercial Drive are more than a year past. But the city's marijuana industry and the culture that supports it remain vibrant, if a touch more low profile, and now the city is pushing Ottawa to legalize the weed.

As part of Vancouver's progressive Four Pillars approach to drug policy -- prevention, treatment, harm reduction, and law enforcement -- the Downtown Eastside is home to Insite, the first officially-approved safe injection site in North America, now in its third and final year as a pilot project. But people are still shooting up on the sidewalks and in the alleys, and the Vancouver Police Department last week announced a crackdown on public injectors -- law enforcement, after all, is one of the Four Pillars. But the city is pushing the federal government toward moving beyond prohibition with the hard drugs of the Downtown Eastside as well. Early last month, the city released a 98-page report, "Preventing Harm from Psychoactive Substance Use," whose two recommendations on public policy changes keep the city on the cutting edge of drug reform worldwide. The city's formal position on marijuana is now that the federal government should "create a legal regulatory framework for cannabis." Regarding all illegal drugs, the city's position is now that prohibition policies should be reviewed to examine their effectiveness and the federal government should "consider regulatory alternatives to the current policy of prohibition for currently illegal drugs." In other words, Vancouver is ready to legalize it -- all of it -- and is telling the federal government to get to it. "We're really just trying to get this on the table. It's a discussion politicians don't want to have,” said Vancouver Drug Policy Coordinator Don McPherson. "When the council approved the strategy, it recommended that the mayor write to the prime minister and seek a meeting to discuss the issue. We've already succeeded with the local politicians; now we have to get the higher-level politicians to act," he told DRCNet. "In every other field of endeavor, you're encouraged to think outide the box, but not with drugs,” McPherson continued. "We're under no illusions, but we are developing a national drug strategy in Canada and we want this to be part of the discussion." Just two weeks earlier, the British Columbia Health Officers Council, representing public health officials from across the province, released its own highly-detailed report, "A Public Health Approach to Drug Control in Canada," calling for a move away from drug prohibition. "Current conditions are right to enter into serious public discussions regarding the creation of a regulatory system for currently illegal drugs in Canada, with better control and reduced harms to be achieved by management in a tightly controlled system," the health officers wrote. "The removal of criminal penalties for drug possession for personal use, and placement of these currently illegal substances in a tight regulatory framework, could both aid implementation of programs to assist those engaged in harmful drug use, and reduce secondary unintended drug-related harms to society that spring from a failed criminal-prohibition approach. This would move individual harmful illegal drug use from being primarily a criminal issue to being primarily a health issue." With momentum for replacing prohibition growing, Vancouver East Member of Parliament Libby Davies, long a drug reform champion, is now ready to take the message to parliament. Or at least she was until the Liberal federal government fell in a no confidence vote and elections were called for next month. "We had been working with the BC health groups and people like Creative Resistance and actually had a draft motion for people to look at," Davies campaign communications director Leanne Holt told DRCNet. "But for the next few weeks, it's going to be on the back burner." "Libby wants to use the Health Officers Council paper to introduce both a motion and a bill calling on parliament to look at regulation," said Vancouver Coastal Health Authority Addiction Services clinical supervisor Mark Haden. "She says it pays to be repetitive." But gaining ground in Ottawa means continuing to build a reform base in Vancouver, said Haden, who helped work on the city's prevention report. "A larger public education process is needed," he told DRCNet. "How do you engage the public to look at the issue? The prevention strategy was a discussion document, and we need to keep it alive in the public eye." In the meantime, drug injecting in the Downtown Eastside is back in the public eye, as Vancouver Police announced their crackdown. Citing community complaints, Inspector Bob Rolls, District Commander of the Northeast section of Vancouver, said the department would begin arresting people shooting up in public and charging them with drug possession. "We have very carefully set up our strategy for this initiative. We have met with our partners, such as VANDU and the Safe Injection Site. Our officers have been spreading the word among the drug users they encounter, warning them this is coming and to start using the Safe Injection Site." The police may have met with VANDU, the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users, but that doesn't mean it has the group's agreement. "The crackdown is not helpful," said VANDU leader Ann Livingston. "They think they're helping people by forcing them to go to Insite, but Insite doesn't have an inhalation room, the nurses there can't help people inject, and it's already operating at capacity anyway. We need a network of sites, four or five of them, four or five blocks apart in the Downtown Eastside. There is a very intense need in this neighborhood, and with some 5,000 addicts injecting, say, three times a day, Insite can handle only about 5% of injections." While Insite can point with pride to its accomplishments -- with an average of around 600 injections a day, published research shows it has reduced both needle-sharing among high-risk users and public shooting up and injection debris, and it has intervened in more than 300 overdoses, losing not a single life -- it recognizes its limits. "It's not realistic to think this one modest site could provide support for every injection drug user and every injection in the neighborhood every day," said Chris Buchner, HIV/AIDS Services Manger for Vancouver Coastal Health. "The next logical step would be to extend these services as widely as we can for people who might need them." But that's not likely to happen until Insite's initial three-year trial is over next September, Buchner said. "We need to let the full pilot period run its course. While we've learned some specific things about what an intervention like this can offer in reducing HIV risk behavior, we still lack rigorous data on overdose prevention and on the actual impact on the HIV incidence rate," he explained. "We know we intervene in about 200 ODs every year, but we haven't yet quantified how many deaths we've prevented. And while we know we have modified HIV risk behavior, we don't actually know yet if people who use Insite have a lower incidence than those who don't. These are key goals, and our research team is working hard to get the data." As for the police crackdown on public injecting around the site, Buchner was pragmatic. "The police support us from the highest levels on down, but they have a very specific culture, and all this talk about disease, health, and addiction is a stretch for them," he said. "But we can't be aggressive and adversarial, we need to be understanding and look at this as a learning opportunity." "I was disappointed with the crackdown, but pleased with the language they used," said Haden. "When they announced it, it was all about support for the safe injection site, 'We're going to make people go to the safe injection site,'" he said. In the de facto division of labor on the Downtown Eastside, that leaves VANDU to make a stink, and it has. The group has held two protests, one in front of Insite and one in front of police headquarters on World Aids Day. VANDU has a slightly different take on the police. "The police union has never supported the safe injection site, and now the police are testing the water, seeing if anyone will say anything if they violate these agreements they made. It's really trying," said Livingston. "The public thinks this has been dealt with. They think we have safe injection sites now, but we don't -- we have one site that's not big enough to impact the health of addicts or the community by reducing public drug use. In that sense, at least, the loudly announced crackdown is a good thing because it is getting the public's attention. The people of Vancouver support safe injection sites, and they need to know we don't have enough of them." And so it goes. While Vancouver is moving forward not only on Four Pillars but also on agitating for an end to the current drug prohibition regime, the nitty-gritty of crafting an enlightened policy in the twilight of prohibition continues.

|