DRCNet

Book

Review:

"Tulia:

Race,

Cocaine,

and

Corruption

in

a

Small

Texas

Town,"

by

Nate

Blakeslee

(2005,

Public

Affairs

Press,

450

pp.,

$26.95

HB)

12/2/05

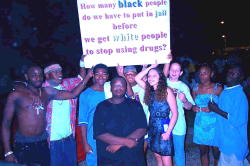

Regular Drug War Chronicle readers are undoubtedly familiar with Tulia, the small Texas Panhandle town where an itinerant undercover cop almost single-handedly sent a fifth of the town's adult black population to prison on bogus cocaine sales charges. We've been reporting on the bust and its fall-out since October 2000, a little more than a year after the early morning raids that set events in motion, and when the first faint rumblings about massive drug war injustice in Tulia were beginning to appear on the national mediascape.

The book is a page-turner. In 450 pages, Blakeslee weaves a virtually seamless narrative that brings the characters to vivid life, from the mostly young, mostly black men who were the real victims in Tulia to the staunch, church-going sheriff who ordered their arrests and the shiftless drifter with a badge and a racist attitude whose lies sent many of them to prison. He also paints a stark portrait of Tulia itself, a weathered West Texas town whose best days are behind it and whose white population still has problems accommodating itself to the blacks who now make up a tenth of the town's 5,000 souls. Blakeslee's story is fast-moving and riveting, as he moves with ease from character portraits to explanations of legal arcana and dramatic courtroom scenes. In "Tulia," Blakeslee tells how local iconoclast Gary Gardner, who became an outcast after suing the local school district over its drug testing policy, played a crucial early role, his sense of smell sharpened by his earlier run-in with the Tulia establishment and his near obsession with the mass bust providing the documentation that eventually attracted journalists, civil rights activists, and attorneys from Texas and around the nation to the cause. Readers also meet white Tulians the Friends of Justice, whose faith-based belief in social justice impelled people like Alan Bean and Charles Kiker to risk becoming outcasts as well for demanding justice for people most of the white community believed rightfully convicted. And the lawyers, the ones who defended the early cases memorable mainly for their varying mixtures of incompetence and indifference, as well as the ones who emerge as heroes in the tale, like feisty Amarillo defense attorney Jeff Blackburn and still-wet-behind-the-ears NAACP Legal Defense Fund lawyer Vanita Gupta, who orchestrated a high-dollar legal onslaught the likes of which Tulia had never seen before. Reading Blakeslee's rendition of the climactic hearings where Gupta, Blackburn and their team shred the reputations not only of Tom Coleman, but also Sheriff Larry White, who hired Coleman despite his poor history in law enforcement and lied about it in court, and District Attorney Terry McKeachern, who hid evidence of Coleman's misdeeds from defense attorneys, is as entrancing as any Grisham novel. Similarly, Blakeslee's description of Tulia victims like bald, hulking Joe Moore, the godfather of the town's black community McKeachern called a "drug kingpin," are sensitively drawn, warts and all. With the skill of a talented journalist, Blakeslee has created a masterful portrayal of the town, the people, the narc, and a legal system that seems to epitomize the worst notions of small town justice. But he does more than that. His narrative is interrupted for one chapter in the middle of the book, but it is an invaluable break because that chapter is devoted to the larger pork-barrel politics of the drug war. Tulia narc Tom Coleman was the employee of a Texas law enforcement anti-drug task force, one of up to 45 that covered the state. As Blakeslee explains, those task forces are the creation of a federal program, the Byrne grants program, explicitly designed to generate and fund such task forces across the country. What happened in Tulia was exceptional only for its brazenness and the resulting spotlight that revealed the moral corruption and injustice at the very heart of the drug war. Thanks in part to Blakeslee's earlier reporting, the Tulia story has a largely happy ending. The villains received their comeuppance, the victims regained their freedom (some for only awhile), and -- will wonders never cease? -- the Texas legislature was actually shamed into passing limited reform bills reining in the drug task forces. Their numbers are starting to decline now in Texas, caught as they are between increasing regulation from Austin and decreasing funding from Washington. But "Tulia" also tells a larger tale. It is America's war on drugs writ small. The essentially injustice of America's drug war is not just in Tulia, not just in small town America, not just in Red State America. It's everywhere. "Tulia" should be required reading for every criminal justice major, ever prosecutor, every judge in the land. And it makes damn good reading, too.

|