| Drug War Chronicle:

How did you end up doing 15-to-life?

Tony Papa: I was married

with a six-year-old daughter and had a radio installation shop in the East

Bronx. I was in a bowling league, and one of my teammates asked me

why I kept showing up late. I told him my car was breaking down and

I didn't have any money to fix it. Then a couple of weeks later,

another guy from the bowling alley was dealing drugs up in Westchester

County, and he met with me and asked me if I wanted to make some quick

money. He offered me $500 to run a package up to Mt. Vernon from

the Bronx, and it was like dangling a carrot on a stick. At first

I said no, but things got desperate, and when that happens you do desperate

things. I was tapped out, I owed rent money, I'd been gambling at

bowling allies and was on a bad losing streak. I thought the American

dream was making a fast buck, and I saw a chance to do that.

I delivered the package and

walked into a police sting. The guy who set me up had three sealed

indictments, he was working with the police, and the more people he got

involved the less time he would get. That one-time delivery turned

out to be a nightmare. I did everything wrong. I was ready

to take a plea bargain that would have sent me up for three to life, but

I didn't want to go to prison, I didn't want to leave my wife and daughter.

So I let another lawyer convince me to go to trial. That lasted a

couple of days and it ended with what I call the St. Valentine's Day Massacre

on February 14, 1985, when I was sentenced to two 15-years-to-life sentences.

I spent a couple of months

at Valhalla jail in Westchester County before going to state prison, and

I used the time to prepare myself for my trip upstate. I got to see

what the system was about, how prisoners pretended they had drug habits

to get methadone, how the prisons tried to control the populations with

psychotropic drugs. In July 1985, I was sent to Sing Sing.

It was really the belly of the best, a maximum security prison. Stabbings

were common, there was violence all over the place, drugs were rampant.

In Sing Sing, if you didn't come in with a habit, you certainly left with

one. The guards brought the dope in. It was a cesspool.

In 1988, they busted a female guards' sex and drug ring, and the newspapers

starting calling it "Swing Swing, the home of sex, drugs, and rock 'n'

roll." There was a block behind the gym known as Times Square.

You could get anything there -- sex, drugs, knives, TV sets -- all you

needed was money. Sing Sing was a wild, dangerous place.

Chronicle: Those are

the kinds of conditions that destroy people's souls. Too many people

come out worse than when they went in. It's as if we've created a

system designed to generate mass pathology. What did you do to avoid

falling into the pit?

Papa: I transcended

the negativity by discovering art. Another prisoner turned me on

to painting, and I got hooked. It was like this very positive energy.

Prison is the most existential environment around; when you're sitting

most of the time in a 6' x 9' cage, you really have a chance to get into

yourself and figure out who you are. Through studying art, I introduced

myself to the masters, I got turned on to Picasso and "Guernica."

A woman named Vick saw some of my work at a local art show, and we corresponded.

I sent her a painting, and she wrote back and said there was more to art

than frilly white dresses. She turned me on to the Mexican muralists

-- people like Diego Rivera, Jose Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros --

and following their example, I started to use my art as a vehicle to fight

the system on the side of the oppressed against the oppressor.

I also educated myself.

I got three degrees in prison, including a masters' degree from the New

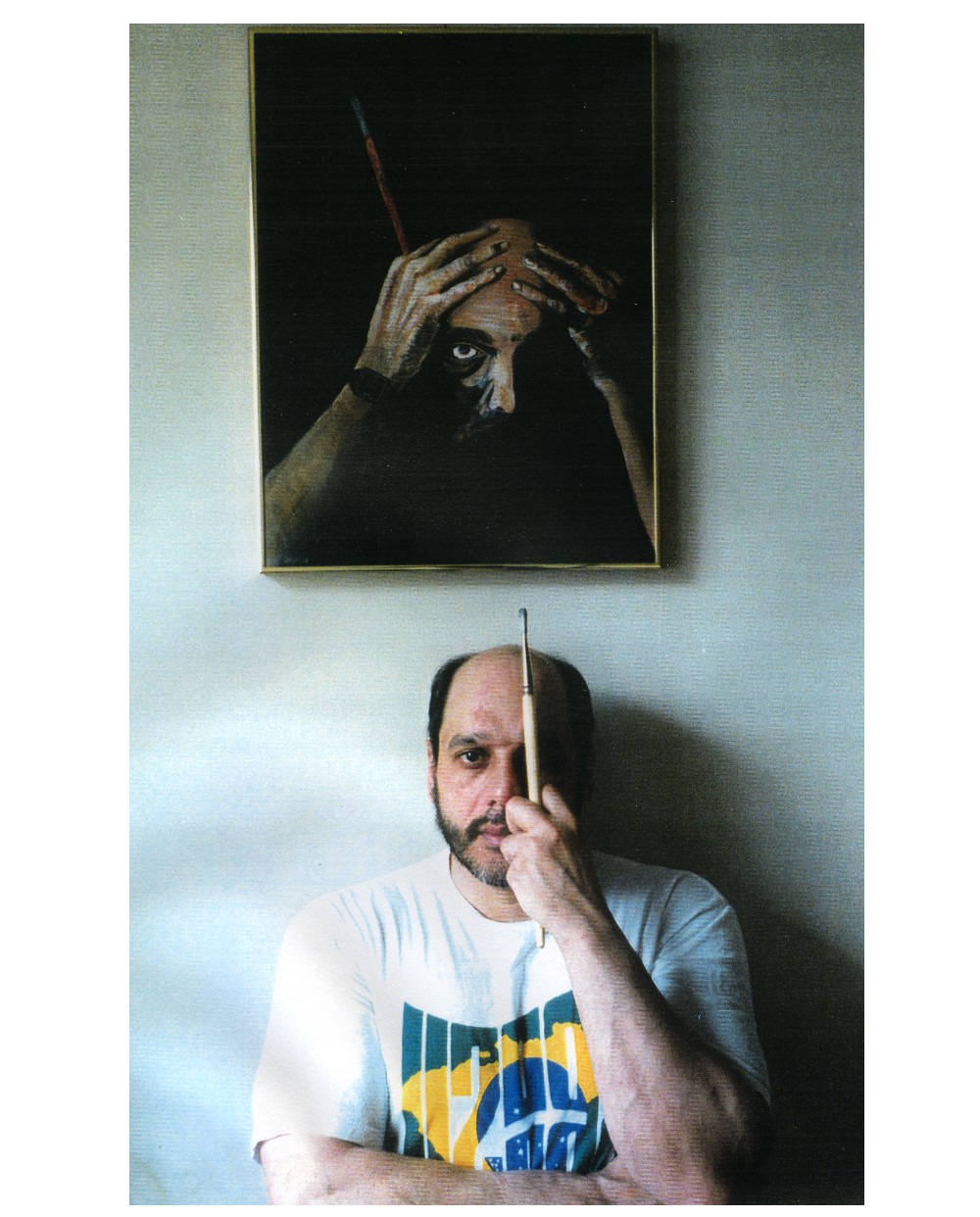

York Theological Seminary. In 1988, I was sitting in my cell and

picked up a mirror and saw a guy who was going to spend the most productive

years of his life in a cage. I picked up a canvas and painted a self-portrait.

I called it "15 Years to Life," and for me and many others, it captured

the essence of prison. From then on, I began painting political pieces

-- death penalty, felony disenfranchisement, issues that affected my community.

Chronicle: Your art

ultimately led to your freedom. What happened?

Papa: Seven years later,

the Whitney Museum wrote the prison asking for work by a prisoner to show

in a coming exhibit, a retrospective of Mike Kelley, a conceptual artist

from LA. The piece would be exhibited in the art capitals of the

world. Basically, I sent my work, and Mike Kelley chose my "15 Years

to Life" self-portrait. I see that letter from the Whitney as angelic.

I knew this was the chance for me to get out of prison, to paint my way

out of prison. I got a tremendous amount of publicity from the show,

and I worked it. I became a PR wizard, I started writing to journalists,

and I had my own PR list. I finally hit pay dirt when Prison Life

covered the story. That was Richard Stratton, who later went on to

edit High Times before it ran into trouble this year. After Prison

Life, other publications followed.

I'd been in 10 years, I'd

exhausted all legal remedies; this was my only hope. I worked it,

and I started getting publicity and became sort of a cause celebre.

The prison was getting flooded with interview requests, then I had an exhibition

at the seminary, which generated more publicity, including the New York

Times and the New York Law Journal. Danny Schecter talked about my

case on his show "Rights and Wrongs" when he did a show on the drug war.

Every article, every media mention was important, another step closer to

winning clemency.

Then, a week before Christmas

1996, I got called into the security office -- you only get called there

if you fuck up. I figured it was because of the political content

of some of the work I was doing. They were doing body cavity searches

on me, and I was outraged and drew a series of drawings of this experience

and posted them on cut-outs of the actual prison security directives.

The prison guards confiscated them. They said I was smuggling out

directives, but it was really because they didn't want me to expose the

dehumanizing aspects of prison life. I remember sitting on that bench

feeling defeated, thinking I had blown my chance for freedom. But

the deputy warden came out and said he just got off the phone with the

governor and I had been granted clemency. I started sobbing like

a baby.

Chronicle: You mentioned

"Guernica" and the political influence of the Mexican muralists.

Did you have any politics before you went to prison?

Papa: No. The

greatest gift I got from being in prison besides the art was the birth

of my political life. I knew when I came out that I had to do something

to stop this injustice. I started going to Albany with different

groups, but I saw I was wasting my time. The politicians would say

they knew the Rockefeller laws didn't work, but they couldn't afford to

be seen as soft on crime. I realized it was fruitless to try to change

the drug laws in New York from the top down. It would have to come

from the bottom up, so I helped found the New York Mothers of the Disappeared,

and we became a leading group agitating against the Rockefeller laws.

These days, I work with the

Mothers, but I also work with other groups and individuals. I got

hip-hop mogul Russell Simmons interested in the issues, and I'm working

with Andrew Cuomo. I did commercials with Tom Golisano when he ran

for governor. I also work with groups active at the federal level,

like Families Against Mandatory Minimums and the November Coalition.

I'll be working with Cuomo on his new project Help USA. And of course,

I still work with local groups, like Justice Works and the Correctional

Association of New York. I continue to use my pen and my brush.

Art is a great vehicle to get public awareness and get people involved.

Chronicle: You've got

a book coming out later this month called, appropriately enough, "15 to

Life: How I Painted My Way to Freedom." What are you trying to achieve

with this book?

Papa: One of the things

I want to do is try to jumpstart the movement to repeal the Rockefeller

laws. I hope this book will give people an idea of what goes on in

the prisons of New York and around the country, how they're full of nonviolent,

first-time drug offenders, how people are demonized for drug use.

We're going to have a big book launch at the Whitney [Museum] on the 18th

[of October], which will be hosted by Help USA. It'll be an effort

to raise public awareness of different social justice issues, from the

environment to the death penalty to the Rockefeller laws.

New York's legislative process

is dysfunctional, and the laws don't change because of the process.

The governor and the leaders of the legislature all say they want change,

but nothing happens. But knocking off DA Soares in Albany a couple

weeks ago (https://stopthedrugwar.org/chronicle-old/354/shocker.shtml)

is big. It's the DAs who are blocking change, and a victory like

this shows that if you continue to support these draconian drug laws that

everyone wants to change, you just might lose your job.

As an activist, it's my job

to do everything possible to bring this issue to the public. My job

is to find ways to make the drug war issue dramatic and memorable, like

a movement poem or a haunting melody. I hope my book succeeds in

doing that. |