The effort to wipe out opium production has achieved limited success at best, hurt the poorest Afghans, and riddled the government with corruption from top to bottom, according to a comprehensive report released Tuesday by the United Nations and the World Bank.

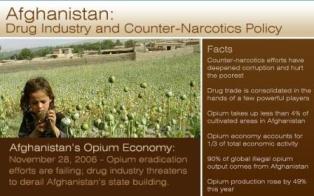

Afghanistan produced 6,100 tons of opium this year -- enough to make 610 tons of heroin -- and is line to produce even more next year. Opium accounts for at least one-third of the Afghan GDP, and profits from the trade end up in the pockets of government ministers, warlords, traffickers, and Islamic radicals alike. But with opium employing 13% of the workforce, it is also farmers, rural laborers, transporters, and gunmen -- and their families -- who earn a living off the trade.

Efforts to eradicate opium crops have the greatest adverse impact on the poor, the study found. If alternative development is going to take hold in the country, planners must keep that in mind, said Alastair McKechnie, World Bank Country Director for Afghanistan.

"Efforts to discourage farmers from planting opium poppy should be concentrated in localities where land, water, and access to markets are such that alternative livelihoods are already available," he argued. "Rural development programs are needed throughout the country and should not be focused primarily on opium areas, to help prevent cultivation from further spreading."

"The critical adverse development impact of actions against drugs is on poor farmers and rural wage laborers," said William Byrd, World Bank economist and co-editor of the report. "Any counter-narcotics strategy needs to keep short-run expectations modest, avoid worsening the situation of the poor, and adequately focus on longer term rural development."

"History teaches us that it will take a generation to render Afghanistan opium-free," said Antonio Maria Costa, executive director of UNODC, who used the release of the report to argue for a dual approach of aid and repression. "But we need concrete results now," he said, proposing to double the number of opium-free provinces from six to 12 next year. "I therefore propose that development support to farmers, the arrest of corrupt officials and eradication measures be concentrated in half a dozen provinces with low cultivation in 2006 so as to free them from the scourge of opium. Those driving the drug industry must be brought to justice and officials who support it sacked."

Despite his tough talk, what Costa did not say was that his proposal amounted to a recognition that effective eradication is impossible in the primary opium-producing provinces of the country this year. Although the World Bank-UN report barely mentions them, a resurgent Taliban, grown rich -- like everyone else -- on the profits of protecting the trade, has been a big reason why.

"Now that the control is more in the hands of the Taliban and their supporters, there is less hope for eradication and more people are involved and looking to make money, so the chances for success are not good," said Raheem Yaseer of the University of Nebraska-Omaha Center for Afghanistan Studies. "I am less optimistic than I was even a few weeks ago," he told Drug War Chronicle. "The British were talking a lot about concentrating on eradication in Helmand province, but they didn't do much because they were too busy fighting the Taliban. If nothing is done, it will be worse next year."

Those trying to get rid of opium will be up against not only the Taliban but also elements of the government itself. "This report emphasizes the way counter-narcotics efforts have been manipulated and perverted to result in a concentration of power," said Brookings Institution expert on illicit substances and military conflict Vanda Felbab-Brown. "Governors, provincial chiefs, district police chiefs -- people like these were tasked with eradication or interdiction, but they used their power to target their opposition or competition," she told the Chronicle. "Essentially, local actors were able to capture counter-narcotics efforts and use them to not only consolidate control and power over the drug industry, but also increase their political power. Counter-narcotics policy is being perverted to help create a new distribution of power in Afghanistan."

The report also confirms some emerging trends that signal even more trouble in the future, Felbab-Brown noted. "One of the things confirmed in the report is the increasing concentration and hierarchical organization of the drug economy in Afghanistan," she said. "This has been a trend that the report confirms is taking place. The warlords and commanders are vanishing from the visible drug economy. They no longer trade directly; these guys with positions of power inside the government are instead now taking protection money. They are not directly participating in the trade, but they are still participating."

The UN's Costa can call for six more opium-free provinces and the Americans and the Karzai government can daydream about success through chemical eradication, but this sobering document from the sober people at the World Bank and the UN is just the latest to send a strong signal that the global drug prohibition regime has tied itself in knots in Afghanistan.

This work by StoptheDrugWar.org is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International

Comments

What about legal uses for Heroin

Can someone explain to me why heroin is not used for pain management, particularly in hospice or for the terminally ill in other settings?

It is much more practical to find legal avenues for drugs than attempt to ban growth and contribute to crime and illegal traffic.

In reply to What about legal uses for Heroin by Anonymous (not verified)

heroin for pain management

This is a good question -- even in the context of a prohibitionist system there is no rational justification for treating heroin differently from morphine as far as pain management. Heroin is derived from morphine through a chemical process. There are other opiates that are legal for medical use that are as strong or stronger than heroin.

Unfortunately, pain treatment is itself in a painful situation. See our archive on the topic at http://stopthedrugwar.org/topics/drug_war_issues/medicine/under_treatment_of_pain for our most recent coverage of the issue. So pain patients face much bigger obstacles to obtaining appropriate treatment than the ban on heroin prescribing -- if heroin is made legally available for medical use, but the overall pain treatment situation does not change, it will just be another drug that isn't used in most of the situation where it should be.

Conversely, fixing the pain prescribing problem for the other opiates will do most of what is needed for pain patients, though some patients would be better served with heroin. I think it is important to make heroin available for pain treatment, but there's a bigger war going on in that arena.

David Borden, Executive Director

StoptheDrugWar.org: the Drug Reform Coordination Network

Washington, DC

http://stopthedrugwar.org

Sorry if I tire of all the

Sorry if I tire of all the official posturing regarding the drug trade. McCoy (The Politics of Heroin) has rendered the facts well enough for any willing reader to be able to understand the abject dishonesty involved in all official pronouncements.

In our dominator societies anyone with a weakness or disability is considered fair game for gangster exploitation, children, women, the poor, illegal aliens, the lonely and depressed, and most dramatically, people in pain. The heroin trade is not only very, very big business, but profits are the glue that holds together the financial and intelligence networks that keep the insane system, that is euphemistically called "the status quo," together and makes, to one degree or another, slaves of us all.

People in pain, physical or mental, greatly need narcotics and will seek them out at virtually any price. Ergo, a black market will produce the greatest profits. As long as gangsters are allowed to control the world this will be the program.

Herb Ruhs, MD

Afghanistan Narcotics Diplomacy

âWe at the Department of State will do our part to use our existing authority to make our foreign assistance more effective and to enhance our ability to serve as responsible stewards of the American taxpayersâ money.â Condoleezza Rice

Sheâs on to something, but what kind of economic diplomacy is available within 'our existing authority'?

A not so âdismalâ Economics idea!

David Warsh writes that individual non-rival goods are well described as ideas. Ideas can used over and over and by more than one person (or nation) at a time. A non-rival good, in essence, is a design, a recipe, formula, blueprint, procedure, technique, arrangement or text. You catch the drift. Think of ideas as bitsâideas that can be written down and encoded in a computer to be used simultaneously by any number of persons. Lots of these bits added together make up what we call knowledge. And it is the non-rivalry of knowledge that is the engine of globalization, so that when nations educate their citizens, they also allow them to participate in global markets, an asset previously denied before their willingness to learn. With so many people and nations now eager to learn and compete, that is what globalization is all about.

This application of a non-rival good aids both learning and globalization, particularly in the poorest of nations, specifically nations that cultivate narcotics producing plants, like Afghanistan and Colombia. Concurrently, this plan devastates narcotics supply and terrorist, insurgency and criminal revenues.

The ânot so dismalâ non-rival idea is this: Rich nations that are narcotics users can profit from paying poor nations ânot to cultivate narcotics producing plants.â allowing the poor nations to benefit from the vast price gap between rich and poor nation cost structures. Hereâs how that cost difference can work.

Everything costs more in rich nations. Everyone is paid more in rich nations. Take rich nations and Afghanistan as a comparison. Afghanistan produces 92% of the worldsâ opiates. For opiates derived from Afghan poppies the 30 richest nations of OECD pay a âsocietal costâ of $217 billion dollars annually. Afghan farmers, according to President Hamid Karzai, get $700 million dollars. This huge gap represents a rich nation opportunity to end opiates cultivation at no cost! How?

When the cost of a societal problem (be it cancer, energy costs, education or narcotics) is substantially reduced, or better yet, eliminated, the costs previously spent are saved in the degree to which the problem is eliminated. If Afghanistan has an incentive to end poppy cultivation, all rich nation savings are available to donors for alternate uses. Price gap differentials allow donors to realize a huge profit.

Therefore, in the case of Afghanistan, one third, $2.8 billion of their GDP, is represented by poppy cultivation. If rich nations replaced that income, paid former poppy farmers, and added another $2.8 billion for education, etc., and did it for a long enough period, letâs say ten years for a measured adjustment to take place, grantors would gain a net savings of $211 billion annually, or $2.1 trillion dollars in ten years. That is an example of how a non-rival good can be utilized. That also means the same idea can be used in places like Colombia, the source of almost 100% of US consumed âhard drugs.â

A more detailed proposal is available on request at [email protected] Thank you!

Afghan poppies can be peacefully marketed

The eradication program must surely devastate any goodwill of the Afghan people towards America. Imagine if it were YOUR crop and YOUR livelihood and YOUR family that suffered losing your crop and investment to powerful foreign invaders!

The U.S. should just buy the damn poppies and produce legitimate morphine. Morphine would then become cheaper and that will help hospitals and patients worldwide. The Afghan farmers will no longer fear for their crops and livelihood if we instead do business together and buy their home-grown product. Should be not be business partners? The Afghan people will be happy growing a valuable crop and everybody will be happy to be making money.

Add new comment