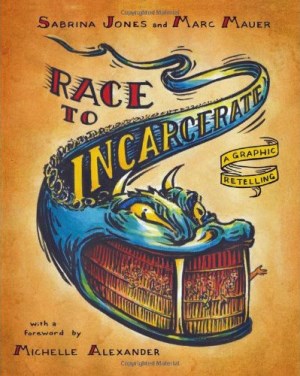

Race to Incarcerate: A Graphic Retelling by Sabrina Jones and Marc Mauer (2013, The New Press, 111 pp., $17.95 PB)

Marc Mauer, the executive director of the The Sentencing Project, a Washington, DC-based nonprofit devoted to reforming harsh sentencing practices and the way we think about crime and justice, first published the groundbreaking Race to Incarcerate back in 1999. With clinical precision, Mauer showed how -- and why -- our prison population began skyrocketing in the 1970s, driven less by crime than the politics of "tough on crime" and "tough on drugs," and how the issue of crime was inextricably interwoven with issues of race and class.

As Michelle Alexander, author of The New Jim Crow notes in her forward to this edition, she used Race to Incarcerate as an organizing tool, sending copies off to people who could wade through and benefit from its number-crunching and policy analysis. But she generally didn't send it to young or uneducated people, relying instead on videos, magazine articles and the like. A Graphic Retelling is designed to be accessible to people who aren't policy analysts or academics, and it succeeds impressively.

With its appropriate dark illustration by graphic artist Sabrina Jones, the graphic version of the book tells the complex and convoluted tale of America's incarceration obsession in a way that is easy to grasp, yet as powerful as paragraphs of dense text -- if not more so. With the help of Jones, Mauer's astute and pointed analysis leaps off the page in easily digestible and visually pleasing -- if sometimes disturbing -- imagery. How better to show (rather than tell) America's position as the world's leading incarcerator than a graphic of men crammed into tiny boxes piled atop more men crammed into tiny boxes in a pile that stretches to the sky?

Mauer and Jones take the reader/viewer on a tour of American punishment going back to the colonial era, when imprisonment was rarely used -- physical punishments, such as whippings or the stocks were instead the norm -- and the first "reform," the "Pennsylvania model," where penitent prisoners resided in a penitentiary, locked in their cells alone all day with their work and their Bibles, to reflect on the error of their ways. Advanced by the Quakers and seen as a humane alternative to physical punishments, the "Pennsylvania model" laid the groundwork for the prison system that has metastasized into the present-day American gulag.

But the "Pennsylvania model" had its critics early on, including Charles Dickens, who called the enforced, prolonged solitary confinement "worse than any torture of the body." Still, a century and a half after Dickens, the penitentiaries endure, and so does the massive use of solitary confinement, even though human rights groups qualify it as a human right abuse.

Race to Incarcerate really takes off, though, in the 1970s, when the prison population, which had been relatively stable for decades, also began taking off. Frightened by the tumult and turmoil of the 1960s, American voters elected "tough on crime" Richard Nixon as president, and the race to incarcerate was on, only to accelerate under Ronald Reagan, and continue full speed ahead under Democratic and Republican administrations alike until the early years of this century.

Along the way, we revisit the draconian Rockefeller drug laws of the 1970s, the model for mandatory minimum sentencing that was to sweep Washington and state capitals in the years to come, as well as successive -- and successively more harsh -- federal drug and sentencing laws that have stuffed our prisons full of nonviolent, low-level drug offenders.

Many of those nonviolent, low-level drug offenders we pay billions to keep behind bars are poor people of color. Too many. A disproportionate number, given the percentage of black people in the population and their rates of drug use (about the same as whites). Mauer shines here with his analysis of the race and -- gasp! -- class dimension of mass incarceration, and the shameful failure of the American political system to respond to social problems with anything other than a prison cell, especially if you happen to be the scary black male "other."

America's imprisonment binge has also inspired a contemporary reform movement, of which Mauer is both member and narrator. And, as he notes in a preface to the new edition, that movement is gaining ground. The overall prison population is now stabilized, if not actually declining, thanks to sentencing reforms in the states and, to a much more limited degree, at the federal level. (The states have had to deal with their budget crises by making real policy choices, such as reducing imprisonment levels; the federal government, on the other hand, simply prints more money and goes on its merry way.)

But even with the progress that has been made, America remains the world's unchallenged leader in imprisoning its own people. Eliminating drug prohibition would cut our prison population by about a fifth, but we would still be the world's leading jailer even then. It's not that Americans are more criminal than anybody else; it's that we lack the will or the imagination to come up with more humane solutions to our social problems -- and some politician can always count on gaining support by playing to fear and the "lock 'em up" vote.

The tide may, finally, be beginning to turn, but there are many, many battles left to fight. Race to Incarcerate: A Graphic Retelling is a perfect tool for educating the young and the non-wonkish about the issues involved and the forces involved in that All-American urge to punish. This book deserves a place in the high school class room, among youth groups, and among those hoping to educate and mobilize for positive change on crime, race, class, and social justice issues. It is a powerful tool for good.

This work by StoptheDrugWar.org is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International

Add new comment