With US public support for marijuana legalization now at the 50% mark, and state legalization efforts now starting to come to fruition, people are naturally talking about it. Academics at RAND and elsewhere recently came out with a book, "Marijuana Legalization: What Everyone Needs to Know," discussing the wide range of issues impacted by legalization and that will come into play affecting how it will play out. (We are sending out copies of this book, complimentary with donations, by the way.)

"It seems to me that we should move to authorize exports," [governor of the the violence-plagued border state of Chihuahaha Cesar] Duarte [an ally of Pena Nieto] told Reuters in an interview. "We would therefore propose organizing production for export, and with it no longer being illegal, we would have control over a business which today is run by criminals, and which finances criminals."

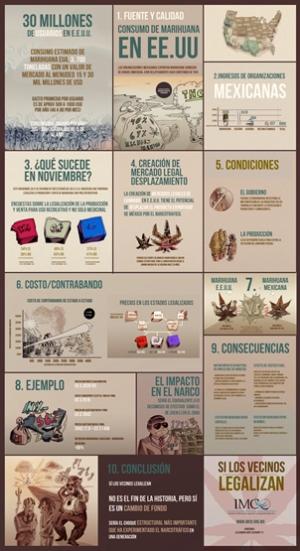

And as The Economist noted last week (hat tip The Dish), the Mexico City-based think tank Mexican Institute for Competitiveness (IMCO) believes that legalization may cost the cartels big time. IMCO estimates that Mexican drug trafficking organizations earn $2 billion per year from marijuana, with $1.4 billion of it going to the US. Significantly, IMCO doesn't just think that legalization by the US and Mexico would cut off the cartels from those funds. They have speculated that marijuana grown in Washington and Colorado (particularly Colorado) might be diverted and sold in other states, with a dramatically lowered cost made possible by legalization causing prices to drop elsewhere as well. Lower prices in turn might lead US marijuana users who now buy Mexican weed to switch to marijuana grown in the US instead, even if it's still illegal in their own states.

I am skeptical that we will see that kind of price drop just yet, in the absence of federal legalization, even in Washington or Colorado. It hasn't happened yet from medical marijuana, even though marijuana grown for the medical market is just as divertable as marijuana grown for the recreational market may be -- the dispensaries themselves haven't undercut street prices, partly to try to avoid diversion. Sellers in other states, and the people who traffic it to them, will continue incur the kinds of legal and business risks that they have now. And it is still impossible to set up the large scale farming operations for marijuana that reduce production costs today for licit agriculture. But we don't really know yet.

Now one study is just one study, at the end of the day -- there are other estimates for the scale and value of the marijuana markets and for how much Mexican marijuana makes up of our market. But the cartels clearly have a lot of money to lose here, if not now then when federal prohibition gets repealed -- IMCO's point is valid, whether they are the ones to have best nailed the numbers or not.

It's also the case that some participants in the drug debate, such as Kevin Sabet, have argued that legalization won't reduce cartel violence, because "the cartels will just move into other kinds of crime." But those arguments miss some basic logical points. Cartels will -- and are -- diversifying their operations to profit from other kinds of illegal businesses besides drugs. But it's their drug profits -- the most plentiful and with the highest profit margin -- that enable them to invest in those businesses. The more big drug money we continue to needlessly send them, the more they will invest in other businesses, some of which are more inherently violative of human rights than drugs are.

Some researchers believe that Mexican cartels will step up their competition in other areas, if they lose access to drug trade profits, which could increase violence at certain levels of the organizations. But such effects are likely to be temporary. Nigel Inkster, former #2 person in Britain's intelligence service and coauthor of "Drugs, Insecurity, and Failed States: The Problems of Prohibition," at a book launch forum said he thinks that at a minimum the upper production levels of the drug trade, as well as the lower distribution levels, would see violence reductions. (We are also offering Inkster's book to donors, by the way.)

And it isn't just violence that's the problem. As a report last year by the Center for International Policy's Global Financial Integrity program noted, "[C]riminal networks... function most easily where there is a certain level of underdevelopment and state weakness... [I]t is in their best interest to actively prevent their profits from flowing into legitimate developing economies. In this way, transnational crime and underdevelopment have a mutually perpetuating relationship." The money flow caused by prohibition, accompanied by violence or not, is itself an important enough reason to urgently want to end prohibition as we do, and to reduce the reach of prohibition as much as is politically possible in the meanwhile, as Colorado and Washington have done.

And so Mexican and other thinkers are speaking up, as are victims of the current policy. For all their sakes, President Pena Nieto should not dismiss legalization so quickly. And Sabet and others should not be so quick to try to argue away the impact that the billions of dollars drug prohibition sends each year to the illicit economy has in fueling criminality and hindering societies from developing.

This work by StoptheDrugWar.org is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International

Add new comment