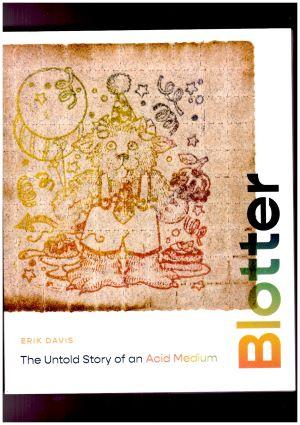

Blotter: The Untold Story of an Acid Medium by Erik Davis (2023, MIT Press, 248 pp., $32.95 PB)

A few decades ago, I made many not-so-rare ventures into the world of blotter acid, eagerly placing one or two of those LSD-impregnated blotter squares on my tongue before blasting off to new dimensions. Many of those blotter hits had no design on them, merely tinted or even plain white paper, but others featured images, some humorous, some esoteric: dancing Grateful Dead bears, JR "Bob" Dobbs heads, psychedelic saints, or just trippy swirls.

In Blotter, journalist and counterculture maven Erik Davis explores and illuminates the phenomenon of blotter acid -- both as a delirium-loaded medium for hyper-potent psychedelic substances and as a drug-free but drug-induced form of psychedelic art. What a long, strange trip it's been, and what memories it stirs up in old hippies of a certain age.

Davis reviews legendary acid producers, with names like Humphrey Owsley and Nick Sands gaining prominent mention, as he describes the evolution of LSD dosing from sugar cubes to pills and blotter paper. But he also introduces a cavalcade of lesser-known LSD producers and blotter acid makers as he traces the evolution of LSD and psychedelic culture from the 1960s to the present.

He has interesting observations about the trade in acid, noting that it was often not (only) profit but a sort of psychedelic evangelism or militance that impelled the distribution of the consciousness-altering substance. Early adopters believed the acid experience could not only change your consciousness; it could change the world. Sometimes they gave it away for free; not the behavior of your stereotypical dope dealer.

And it was always inexpensive; in part because of that psychedelic evangelism -- the object was not to get rich but to better the world -- but also because of the economics of its production. LSD is so potent that anyone producing even small batches is producing hundreds of thousands if not millions of doses at a time. And it is still a bargain producing a whole lot of bang for $5 or $10 to this day. You can trip for eight hours for less than it costs to buy a hamburger.

While Blotter is a book about psychedelic culture, it is also a book about art. Blotter acid was and remains illegal, but blotter art plays a role in the contemporary art scene. The art blotter contains no LSD but the psychedelic spirit lives within it -- the joy and playfulness, the humor and mysticism and radicality. And it makes fascinating art, which Blotter is full of. There must be hundreds of images of blotter art; the entire second half of the book is little more than images and their descriptions.

Erikson centers his book on San Francisco artist, professor, and occasional federal criminal defendant Mark McLoud, curator of one of the largest archives of blotter art in existence, the Institute for Illegal Images. McCloud played a key role in moving blotter art from the realm of the criminal into the realm of the arts, and successfully fended off the feds by convincing a Kansas City jury that blotter art was art -- not dope (which it wasn't—even blotter that has been doses becomes inert over time as the LSD is exposed to light and air).

He is also an astute commentator on contemporary psychedelic culture, and his final words to the community are worth quoting in full. Remarking on LSD's position as a Western, industrial creation and noting many leaders in activists in the psychedelic space are demanding that Indigenous groups get both a place at the table and a share of the profits, Davis writes:

"Such reciprocity efforts are far from cosmetic. They concretely acknowledge the enormous debt that all psychedelic people owe to those savaged but vital communities whose healers and medicine wizards developed and continue to maintain visionary plant and fungi traditions for centuries and presumably millennia. But we also owe a debt to the hippie freaks, renegade chemists, pranksters, midwives, healers, dealers, guitarists, poets, mystics, burners, artists, and DJs of the deep acid underground. However half-baked, dangerous, or even batshit their practices, these folks -- often low-profile by necessity -- still hold powerful medicine for those of us psychedelicizing themselves within WEIRD societies: Western, educated, industrial, rich, and (more or less) democratic. These folks are our "ancestors" -- even the Hells Angels and bad brujos of the CIA. Acid history may look like a profane mess, but it is also a sacred struggle, and like all such esoteric agons, you have to approach it elliptically through patterns and symbols, and tricksy media that might only send you further into forests of whatthefuck. That's the deeper message of the Institute for Illegal Images, which is not just a collection of artifacts but a wayward memory palace, an iconostasis of initiation and synchronicity, a comic-book collage of igniting signs, and the inevitable cracks between them."

What he said.

This work by StoptheDrugWar.org is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International

Add new comment