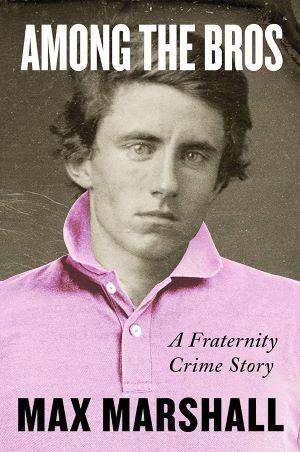

Among the Bros: A Fraternity Crime Story by Max Marshall (2023, HarperCollins, 290 pp. $30 HB)

With their feathered bang haircuts, their pink button-down shirts, and their light-colored slacks, the Greeks examined here were stereotypical frat boys, well-tanned from days at the beach or on the links and ready to party hearty at the drop of a hat. The center of Greek social life, at least on the College of Charleston campus, were the different frats' massive blowout parties, truly drunken (and drugged) debaucheries that involved crazed behavior, property damage, and consequences that seemingly evaporated into thin air.

The book is centered on Little Mikey Schmidt, one of a trio of College of Charleston frat boys who dominated the on-campus and downtown party drug scene in the middle of the 2010s. Between them, Little Mikey and his fellow campus kingpins, Rob and Zack, provided an ungodly amount of Xanax for the gaping maws of frat boys and sorority girls, as well as campus GDIs ("God damned independents") and the denizens of King Street's bar row.

These College of Charleston frats were, in every sense, privileged people. Some of them were ultra-rich, such as the students with last names like Rockefeller and Rothschild, who arrived for the fall semester sailing their yachts down from Connecticut. Those guys were the extreme, though; most of the C of C frat boys were merely sons of the Southern upper-middle class, with parents who were professionals or successful entrepreneurs.

And if those parents wanted to imbue their sons with traditional Southern values, where better than Kappa Alpha, the center of C of C dope dealing at the time, and an order founded as a brother organization to the Ku Klux Klan. The Klan would fight to protect Southern white womanhood, while KA would make it its mission to refurbish Southern white manhood. KA also holds Robert E. Lee in special esteem as a sort of spiritual icon. KA didn't have any Black members, and KA at C of C had never had any Black members. (One campus informant, a Black frat, told Marshall he didn't even bother considering pledging to KA because he had heard it was "predominantly Southern," which is a nice turn of phrase.

Marshall notes that since 1984, when the minimum drinking age rose from 18 to 21, "US law had baked criminality into the lives of fraternity kids." Because, yes, of course, they were going to drink, which theoretically exposed them to a range of misdemeanor charges, and they were going to need fake IDs to get into the King Street bars, which they acquired. In fact, Little Mikey got his start as a criminal by supplying fake IDs for fun and profit so his peers could flout the law and get plastered downtown. But after hearing that the FBI had kicked in the door of an Atlanta ID counterfeiter and qualified him as a national security threat, Little Mikey got out of that business and into the weed business.

A frat in a pot prohibition state like South Caroline was a virtually goldmine for willing dealers, Marshall found: There are lots of kids with excess funds who like to smoke, they live in groups, which facilitates bulk sales; through a combination of naivete and deep pockets, they are unlikely to quibble about the street price of an eighth, they like to stick to fellow frat boy dealers, and if they get caught smoking weed, they have access to good lawyers who can make charges vanish.

Mikey and other campus dealers made good bank from the weed trade, but they made even more when they switched to Xanax, which at the time was becoming exceedingly popular in the campus scene. The generic name for Xanax is alprazolam, a benzodiazepine used to treat anxiety attacks and panic disorders. It is the kind of drug a frat boy's mom might take before a long plane flight.

At C of C, though, Xanax use evolved, first being used as a way to take the edge off Sunday morning hangovers and nerves after a weekend of partying and with academic responsibilities looming. But then, people started taking Xannies before the parties started, having discovered that eating a Xanax and drinking a couple of beers gave them the same effect as drinking eight beers. It was a cheap and efficient way to get way messed up.

And it was hugely popular. Before the death of a frat boy Xanax dealer in an armed robbery blew up the C of C scene, various dealers were taking delivery of 10,000 pills a week. And as use evolved and expanded, so did the means of procuring the drug. At first, black market Xanax came from inside-job rip-offs of pharmaceutical companies and distributors, but as demand outstripped supply, campus dealers turned to the Dark Web, procuring supplies from a Pakistani chemical company. The Pakistani pills were not as high quality as the pharmaceutical ones, but they did the job.

Later yet, the Kappa Alpha guys got their own pill press, found a Chinese supplier for alprazolam, and started cranking out pills at a rate of hundreds of thousand per week. Those pills went all over the South, with the KA dealers sending pledge drivers on routes that covered the major concentrations of fraternities in places like Old Miss, Clemson, and the University of South Carolina, among others.

It all came to an end the way most of these dope dealing tales do: When the frat boy dealer got shot and died surrounded by spilled Xanax, local cops were finally moved to look into things, which led to interest from the DEA, and ultimately to multiple busts. But a funny thing happened on the way to court. Just about everybody skated -- they had daddies who could pay for good lawyers and they were willing, when push came to shove, to rat out their best buddies. (As one campus informant told Marshall, "You can't spell frat without rat.") Little Mike, though, took a principled stance against cooperating with the feds, explainable in part by his fear of having to reveal the cartel sources of the cocaine he was scoring in large quantities in Atlanta. He's in prison now, the only one to get significant time in a major, multi-state drug ring.

Kappha Alpha's C of C chapter was disbanded (it has since returned), the students keep partying, and a new generation of dealers has replaced Little Mikey and his buddies. And the main lesson learned:

"As long as you're one of the boys, you can usually go as hard as you want without having to learn anything. If someone tries to stop your fun, you'll find good lawyers and reasonable judges, and if the outside world sees you as the villain, you can always play the heel."

This isn't a book about drug policy but about power and privilege, and it is great as both true crime and ethnography of a strange North American culture. Read it and weep.

This work by StoptheDrugWar.org is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International

Add new comment