This piece was written for Drug War Chronicle by criminal justice reporter Clarence Walker, [email protected].

What happens if an unsuspecting citizen finds a police-installed GPS tracking device attached beneath his vehicle? As documented in the case of Indiana v. Derek Heuring, things can turn pretty strange.

After they executed a search warrant, the Warrick County Sheriff Department narcotics officers in Heuring's hometown charged him with theft of a GPS tracker, which they had secretly put on his SUV. Heuring never knew who owned the tracker or why the device had been under his vehicle.

A search warrant must clearly show the officers had sufficient probable cause to believe Mr. Heuring had committed a crime to make a theft of the GPS stick. How can people be lawfully charged with theft of property found on one's vehicle, when they didn't know it was there in the first place?

Evansville Indiana criminal attorney Michael C. Keating insisted from the beginning that Heuring did not know what the device was or who it belonged to -- and Keating said his client "had no obligation to leave the GPS tracker on his vehicle."

Desperate to find the GPS, officers executing the search warrant on separate properties owned by the Heuring's family scored a bonus when they recovered meth, drug paraphernalia, and a handgun.

The Indiana Supreme Court Justices threw out the GPS theft charge including the methamphetamine possession charges on February 20, 2020.

"I'm not looking to make things easier for drug dealers," Justice Mark Massa said during arguments on the case. "But something is left on your car even if you know it's the police tracking you, do you have an obligation to leave it there and let them track you -- and if you take it off you're subject to a search of your home?" Massa asked rhetorically.

Deputy Attorney General Jesse Drum answered Massa's question with a resounding "yes".

"The officers did everything they could to rule out every innocent explanation," Drum told the justices, hoping to have the warrants upheld and win the state's case.

This legal groundbreaking story is important for law enforcement authorities, judges, prosecutors, and the public because the charges against Derek Heuring highlight the wide-ranging tactics police often use to justify illegal searches in drug cases, as well as raising broader questions about privacy and government surveillance.

In addition, Heuring's case raises the question of whether the police, even with a warrant, should have the leeway to both place a tracking device on a person's vehicle and forbid the individual to remove it from their vehicle if the person knows the police put it there to watch their every move. For example, if a person discovered a hidden camera in his bedroom should the law require him to leave it there without removing it -- knowing the police are trying to build evidence against them?

In Heuring's situation, the circumstances show how the narcs used a dubious search warrant to recover a GPS tracker claiming that Heuring had stolen it. The police charged him with the GPS theft without evidence that a theft occurred. They were hoping a bogus theft case would suffice against Heuring whom they suspected of dealing illegal drugs.

In a final ruling against state prosecutors that effectively dismissed the cases altogether, another justice opined, "I'm struggling with how that is theft," said Justice Steven David.

"We hold that those search warrants were invalid because the affidavits did not establish probable cause that the GPS device was stolen. We further conclude the affidavits were so lacking in probable cause that the good-faith exception to the exclusionary rule does not apply," Justice Loretta Rush wrote.

Thus, under the exclusionary rule, "the evidence seized from Heuring's home and his father's barn must be suppressed."

"We reverse and remand,'' the Indiana Supreme Court Justices wrote.

How It Went Down

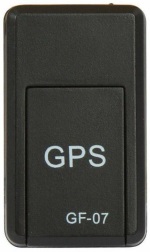

The warrant authorized 30 days of tracking, but the device failed to transmit Heuring's location after the sixth day. Then on the seventh day, the narcs received a final update from the tracker showing Heuring's SUV at his residence. The officers were increasingly puzzled over why they weren't detecting location information three days later. Finally, however, a technician assured the officers that the battery was fully charged but that the "satellite was not reading."

Alarmed over the ensuing problem, Officer Busing decided to check out the happenings with the GPS. Busing drove over to Heuring's father's barn where the SUV was parked. He thought the location of the barn thwarted the satellite signal. Subsequently, the officers saw the vehicle parked away from the barn, and then parked outside of the family's home. Officer Young again contacted a technician "to see if the GPS would track now." The tech informed him, "that the device was not registering and needed a hard reset."

Officers went to retrieve the GPS from the SUV, but it was gone!

The officers discussed how a GPS had previously disengaged from a vehicle by accident, yet still, the device was located because the GPS continued to transmit satellite readings. Convinced the GPS had been stolen and stashed in either Heuring's home or his father's barn, Officer Busing filed affidavits for warrants to search both locations for evidence of theft of the GPS.

With guns drawn, deputies stormed Heuring's home and the barn. Deputies recovered meth, drug paraphernalia, and a handgun. Next, Officer Busing obtained warrants to search the house and barn for narcotics. The officers located the GPS tracker during the second search, including more contraband. Finally, deputies arrested the young man.

Although a jury trial hadn't taken place, Heuring's defense attorney Michael Keating filed a series of motions in 2018 to suppress the seized evidence. Keating challenged the validity of the search warrants under both the Fourth Amendment and Article 1, Section 11 of the Indiana Constitution. Keating's motion argued the initial search warrants were issued without probable cause that evidence of a crime -- the theft of the GPS device -- would be found in either his home or his father's barn. Prosecutors argued the opposite, and the trial court judge ruled against Heuring, thus setting the stage for defense attorneys to appeal the trial court adverse ruling with the first-level state appellate court, arguing the same facts about the faulty search warrants. After hearing both sides, the appellate judges upheld the trial court's refusal to suppress the evidence against Heuring.

Despite the trial court and the lower-level court upholding the questionable warrants the Indiana Supreme Court Justices heard oral arguments from the defense attorney and the attorney general on November 7, 2019. The central point of the legal arguments boiled down to the search warrants. Supreme Court justices pinpointed the fallacies of the officer's search warrants by in their opinion.

The justices concurred, "The affidavits support nothing more than speculation -- a hunch that someone removed the device intending to deprive the Sheriff's Department of its value or use."

"We find it reckless for an officer to search a suspect's home and his father's barn based on nothing more than a hunch that a crime had been committed. We are confident that applying the exclusionary rule here will deter similar reckless conduct in the future", Justice Rush concluded.

Derek Heuring is a free man today. Thanks to common sense judges.

And Another GPS Tracking Case: Louisiana Woman Cold-Busted State Police Planting GPS on Her Vehicle; She Removes It; Police Want it Back

Just last year in March, an alert citizen identified as Tiara Beverly was at home in her gated apartment complex in Baton Rouge, Louisiana preparing to run errands when she noticed something peculiar. She spotted a group of suspicious white men standing near her car. Beverly's adrenaline shot sky-high when she saw one of the cool-acting fellows bend over and placed something under her car.

"I instantly panicked," Beverly told local television station WBRZ. "I didn't "know if it was a bomb, but I found out it was a tracker.

Unsatisfied with Beverly's denial that she didn't have a location on the person they were looking for, the police planted a GPS under her car. Two weeks prior, Louisiana State Troopers visited Beverly's home and harshly questioned her about a personal friend she knew. Again, Beverly vehemently denied knowing the person's whereabouts. Finally, two days later, the officers put the GPS on Beverly's vehicle, Details are sketchy of how the police gathered evidence to arrest Beverly on narcotic-related charges in February 2021. A judge released Beverly on a $22,000 bond.

When Beverly finally determined the GPS was placed on her vehicle by police, she rushed to the local NAACP in Baton Rouge and told her story to NAACP president Eugene Collins. Collins told the reporter he contacted the police on Beverly's behalf and the police immediately demanded Collins and Beverly to return the GPS tracker -- and they threatened her.

"They asked me to return the box, or it could make the situation more difficult for me," Collins recalled.

Civilians are prohibited from possessing or using GPS devices, but they are legal for law enforcement, parole, and probation officers or correctional officials to use, according to Louisiana Revised Statute 14: 222.3.

Police told reporters they had a warrant for the tracking device placed on Beverly's vehicle. However, when the WBRZ reporter asked to see the warrant, the State Trooper's Office declined to produce it, issuing the following statement: "Upon speaking with our detectives, this is part of an ongoing investigation involving Ms. Beverly and a suspect with federal warrants."

The Public Information Officer added, "Further information regarding charges and investigative documents will be available."

"The fact that a young woman can see you doing something like this means you're not very good at it," Collins told WBRZ.

Police in Beverly Tiara's case had a good shot to track her whereabouts, yet they blew it big time. Tiara's case isn't over yet, so we'll be reporting on future developments.

In Derek Heuring's criminal charges, Chief Justice Loretta Rush summed it up best when she said, "There is nothing new in the realization that the Constitution sometimes insulates the criminality of a few to protect the privacy of us all."

This work by StoptheDrugWar.org is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International

Comments

police spy boxes

If I ever find one of those damn things under my car, I'll run over it and they can bitch all they want.

Add new comment