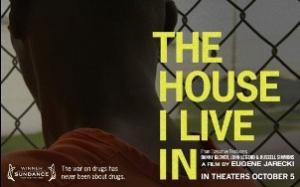

In a conference call Monday morning, filmmaker Eugene Jarecki discussed the impact of his award-winning drug war documentary The House I Live In and where we go from here in the fight to end the drug war and mass incarceration.

Jarecki won the Sundance Film Festival grand jury prize for The House I Live In in 2012. The film made a shattering case against the drug war. Since its release, it has been used as a primer in faith institutions, schools and community-based organizations across the nation.

The drug reform landscape has been undergoing tectonic shifts in the two years since The House I Live In was released. It is possible, Jarecki said, that his film has played a role in shifting public opinion.

"One of the great lies that pervades the public imagination is the Hollywood lie that its movies don't shape the violence in this country," he said. "For Hollywood to pretend that movies have no role in shaping behavior is laughable. There are books that start revolutions. While Hollywood should bristle at the notion that movies create violence -- the violence comes in a society where we don't have health service and the roots of unwantedness can lead to violent behavior -- movies do shape public activity," he said.

"My movie is shaping public activity, and I am reminded by friends that this matters," the filmmaker continued. "A lot of young people will look at Michelle Alexander and say 'I want to be like that,' and that kind of example is extremely precious."

The recognition that the film would be an instrument of social change even influenced the title, Jarecki said.

"The making and handling of the film as a tool for public change and discussion" was important, he said. "We called it House over sexier titles, such as Kill the Poor or just Ghetto. I couldn't get it in a church or prison with a title like Kill the Poor. We had to choose a softer title; we weren't just thinking about the most poetic title, but really, how do we make sure this thing has legs where people all across the country can use it? We didn't want to alienate groups on the ground, and I wanted to make sure there were many groups on the ground doing this important work."

"We've found churches very welcoming, in large part because of our partnership with the Samuel Dewitt Proctor Conference," he said. "They've helped get churches across the country seeing the film, and it stretches far beyond the black church community. It's been very useful and robust. We also live stream the showings themselves to other churches. When we broadcast out of Shiloh Baptist Church, 180 other congregations also watched it."

But while Jarecki intended the film to serve polemic purposes, even he was surprised at the rapidity of the changes coming in the drug policy realm.

"The most significant surprise has been seeing the entire climate of the war on drugs change in the public imagination," he said. "When we started out, it was impossible to imagine any systemic shifts from the top. We see that the entrenched bureaucracies and corrupt interests are never open to negotiation, but the combination of the moral bankruptcy of the war on drugs and its economic bankruptcy -- 45 million drug arrests over 40 years, and what do we have to show for it? -- the catastrophic cycle of waste without achieving goals, unifies the left and the right like no other issue. The left sees a monster that preys on human rights for profit, and the right sees a bloated government program."

The policies of the war on drugs are now vulnerable, Jarecki said.

"Community groups see how it brings unfairness to communities and ravages society, so now, Washington is trying to appeal to the public by being more sensible," he argued. "This policy is vulnerable. While we've joined forces with the Drug Policy Alliance and other organizations to fight at the ground level, we're also seeing shreds of leadership from Obama, Holder, and Rand Paul. This is a moment of enormous vitality for us."

With a few exceptions, as mentioned just above, "the political class is isolated and orphaned as supporting something that doesn't make any sense," Jarecki said. "I thought I was choosing a very tough enemy, but it doesn't seem like much of a worthy adversary. The gross expenditures are hard to defend, they don't have the national security card to play anymore, the drug war has worn itself thin. 'Just Say No' and 'This is Your Brain on Drugs' hasn't worked. Instead, people just see family members with damaged lives."

It's not just in the realm of marijuana policy that the landscape is shifting in a favorable direction. The issue of the racial disparity in the drug war is also gaining traction.

"The condition of understanding the black American crisis of the drug war has moved light years in the last two years," Jarecki said. "Black folks are bizarrely and disproportionately targeted by the drug war, and that's become a common discussion. It's not a rare thing."

"In the black American story, there is an argument to be made that the new Jim Crow established with the war on drugs was the final nail in the coffin of the civil rights movement," he said. "Black people are worse off economically than before the civil rights movement, and this critical viewpoint has become more widely understood."

But it's not just race. The unspeakable word in American political discourse -- class -- plays a role as well, Jarecki suggested.

"We've seen a shift from a drug war that could be described as predominantly racist to one that also has elements of class in it," he argued. "Poor whites, Latinos, women -- those are the growth areas for the war on drugs now. But let's not forget that black America is still essentially the leading link. We haven't shifted the drug war from race to class; it has diversified, it preserves its racism, but has seized market share by broadening into other class populations."

Racism and the war on drugs are only a part of a much larger problem, the filmmaker argued.

"We have to invite the country to begin seriously asking itself what kind of country it wants to be," he said. "What we are really looking at is a society that has bought into the notion that we can entrust the public good to private gain. We have industrial complexes that grip American policymaking in almost every sphere of public life, and the prison industrial complex is one of them. It is simply a crass illustration that you can feed a human being into the machine, and out comes dollar signs. This is a country without compassion, a town without pity."

And while change will come from the top, it will be impelled only by pressure from the bottom up, he said.

"Change comes from groups working together, and you start going down that road by getting out and starting walking," Jarecki advised. "It's an illusion to think we're supposed to be rescued by the government."

We have to do it ourselves.

This work by StoptheDrugWar.org is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International

Comments

One of the 'war on drugs' worse victims

Rick Wershe is currently serving a life prison sentence in the Michigan Department of Corrections for a single (non-violent 1st offense) drug possession conviction from January 1988. When he was arrested he was only 17 years old.

http://clemencyreport.org/richard-wershe-jr-named-michigans-no-1-inmate-deserving-clemency/

http://www.thefix.com/content/story-white-boy-rick-richard-wershe-detroit-corruption70041?page=all

https://www.facebook.com/freewhiteboyrickwershe

Add new comment