New Orleans resident Pearl Bland was arrested and jailed on drug paraphernalia charges in August 2005, just weeks before Hurricane Katrina devastated the city. She pleaded guilty on August 11, and her judge ordered her released the next day for placement in a drug rehabilitation program. Recognizing Bland was indigent, he waived the fines and fees. But Bland was not released the next day. The Orleans Parish Prison (OPP) instead held her because she owed $398 in fines and fees from an earlier arrest. She had one more court hearing in August and a September 20 status hearing was set where in all probability the fines and fees would have been waived.

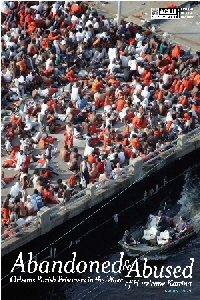

Pearl Bland never got her September hearing. Instead, once Katrina hit, she joined thousands of prisoners stuck in purgatory. After suffering beatings from her fellow inmates in the OPP as deputies shrugged their shoulders, Bland was evacuated, first to the maximum security state prison at Angola and eventually to a jail in Avoyelles Parish. In June, she desperately contacted the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), which in turn contacted attorneys with the Tulane University Criminal Law Clinic, who managed to win her release on June 28. Bland wasnât there for her release hearing, just as she hadnât been present at four previous hearings in the preceding weeks, because her jailers couldnât be bothered to deliver her to court.

"Pearl Bland spent 10 months in prisons around the state because of $398 in fines and fees that her judge would most likely have waived if she had ever gotten to court," said Tom Javits, an attorney with the ACLU's National Prison Project. "But because of the storm and the the response to it, she didnât get her day in court for months, and then only because she sought out help," he told the Drug War Chronicle.

A year after Katrina, thousands of prisoners have never seen an attorney, never been arraigned, never appeared before a judge. Scandalously, no one has a firm count -- or if they do, they're not telling. "Nobody knows the numbers," said law professor Pamela Metzger, who heads the Tulane Law School Criminal Law Clinic and whose students have been going into Louisiana jails and prisons in search of the Katrina prisoners. "When we ask the district attorney's office to assist us with this, just so people can get lawyers, they say it's not their job. Just since June, my students have been able to track down and get released about 95 people," said Metzger. "But we just have no one of knowing how many are in jail."

When the Chronicle asked ACLU of Louisiana executive director Joe Cook the same question, he had a similar answer. "I don't know what the number is. Ask the district attorney," he said.

The New Orleans district attorney's office did not return repeated calls seeking information on the number of people arrested before or after Katrina who have yet to see a lawyer or have a court hearing. Similarly, and perhaps indicative of the state of affairs at the public defenders office, no one there even answered the phone despite repeated calls. (That's not quite true. On one occasion, a woman answered, but she said she was an accountant and no one else was in the office.)

Published estimates of the number of New Orleans prisoners denied their basic rights to counsel and speedy trial have ranged between 3,000 and 6,000.

Part of the problem is the nearly total collapse of the indigent defender system in the city. It was in terrible shape before the storm hit, and collapsed along with the rest of the criminal justice system in the storm's wake. But while authorities were quick to get law enforcement up and running, it took until June for the criminal courts to begin to operate, and the public defenders' office, which depends on revenue from fines to finance its operations, was running on fumes. Now, nearly three-quarters of the public defenders have simply left even though they are needed to represent about 85% of all criminal defendants in the city.

The situation aroused the attention of the US Department of Justice, which in a report released in April concluded that: "People wait in jail with no charges, and trials cannot take place; even defendants who wish to plead guilty must have counsel for a judge to accept the plea. Without indigent defense lawyers, New Orleans today lacks a true adversarial process, the process to ensure that even the poorest arrested person will get a fair deal, that the government cannot simply lock suspects [up] and forget about them... For the vast majority of arrested individuals," the study found, "justice is simply unavailable."

The situation is also beginning to grate on the nerves of New Orleans judges. In May, Chief Judge of the Criminal District Court Calvin Johnson issued an order requiring everyone charged with traffic or municipal offenses to be cited instead of jailed. The city has "a limited number of jail spaces, and we canât fill them with people charged with minor offenses such as disturbing the peace, trespassing or spitting on the sidewalk... Iâm not exaggerating: There were people in jail for spitting on the sidewalk," he complained.

Last week, another New Orleans criminal court judge, Arthur Hunter, made the news when he threatened to begin holding hearings this week to release some of the prisoners held for months without attorneys or court hearings. That was supposed to happen Tuesday, but it didn't. Instead, Judge Hunter postponed the hearing after prosecutors raised concerns.

While disruptions in the system were inevitable in the wake of Katrina, Tulane's Metzger laid part of the blame on the district attorney's office. "They have made some poor resourcing choices and they are hampered by a sort of knee-jerk response that everything has to be prosecuted to the fullest extent. They are not really looking to clear cases; instead they let people sit without lawyers until they're willing to plead guilty," she said. "It's a form of prosecutorial extortion."

It is not just people who were in jail when Katrina hit, but many of those arrested since who have vanished into the gumbo gulag, said Metzger. "Last week we found a man who had been jailed at the Angola maximum security prison since January. He was picked up for drug possession, his only prior was for marijuana, and he's been sitting in one of the meanest prisons in the country without even seeing a lawyer for eight months," she exclaimed. "We won an order for his release. He was supposed to get out Tuesday, but he's still in jail. We just donât know how many more there are like him."

The district attorney's office is not only uncooperative, it is downright obstinate, Metzger complained. "We filed a right to speedy trial claim on behalf of a man named Gregory Lewis who had already served 10 months on a drug misdemeanor with a six-month maximum. The district attorney's office fought that, and their motion actually said, and I quote, 'It's not unreasonable to hold alleged drug addicts in jail longer than other people; it allows the deadly drugs to leave their system,'" she said.

The district attorney's office motion referred obliquely to detoxification, which is ironic given that there is now no such facility in New Orleans. "There is not a single detox bed in the whole city," said Samantha Hope of the Hope Network, a group that is seeking private funding to open a treatment and recovery center in the heart of the city. "Most folks in OPP right now are people who couldnât get access to treatment for an alcohol or drug problem. That's the way it's been since day one," she told the Chronicle. "Rather than criminalize people with an alcohol or drug problem, we need to find a way to give them support. Confronting our money-eating corrections system, our good ol' boy network, and racism, that is hard to do."

The Tulane students have filed some speedy trial cases, but not everyone is fortunate enough to have a Tulane law student working his case so he can file a speedy trial claim. "In order to file a motion for a speedy trial, you have to have a lawyer, and thousands still do not have counsel,' explained ACLU of Louisiana's Cook. "The indigent defense system was broken long before Katrina hit, and now it is just a disaster," he told the Chronicle.

Drug war prisoners make up a significant but unknown number of those doing "Katrina time," said Cook. "It is definitely a significant proportion of them," he said, "but many of them have not even been formally charged. In New Orleans, as in most large urban areas, it's probably safe to say that a plurality of felony arrests are drug-related."

There are solutions, but they won't come easily. "We have to have a public defender's office that is funded with secure, predictable funding," Metzger recommended. "We have to get beyond relying on fines to fund that office. If we had had public defenders, there would have been someone watching to catch the abuses," she said.

"Second, we need to have prosecutors who understand their obligations to the community," Metzger continued. "Their job is not simply to get convictions but to do justice, and what that means will vary according to the individual facts and circumstances. What post-Katrina justice requires is not what justice required before Katrina. If you were living in New Orleans in the fall of 2005 and you werenât drunk or high, there was probably something wrong with you. Everyone was medicated or self-medicating."

Cook had his own set of recommendations for a fix. "First, we turn up the heat. I just visited the DA this morning and asked him to speed up processing," he revealed. "We want to ensure there is a coordinated emergency evacuation plan for all the prisons and jails and we've asked the Justice Department's civil rights division to look at what happened at OPP and since. Part of that will be looking at why these people didnât get defense counsel or have their day in court."

Turning up the heat is precisely what one recently formed community group is trying to do. And it's not just the prosecutors and public defender system it is targeting. "The police department has taken a new view of who belongs in the city now, and that view doesnât include poor black people," said Ursula Price of Safe Streets, Strong Communities, a group organizing people who were in the jail or otherwise brutalized by police. Safe Streets, Strong Communities is running two campaigns, one to strengthen the indigent defender system and one about improving conditions at the jail itself. "They tell our members 'you shouldnât have come back, we don't want your kind here,'" she told the Chronicle. "Race is an issue, economics is an issue, and our teenage boys are bearing the brunt of it. They are harassed all the time by the police."

It is a matter of choices, said Price. "We have as many cops as before the storm, and half as many people, and we just gave the cops a raise. The city finance department deliberately spends the vast majority of its money on public safety, and then there is nothing left for social services, which are deliberately being sacrificed," she said. "But I'm encouraged because the community is starting to take note. When people found out we were spending half a million dollars a week on the National Guard without it having any impact, they started to get mobilized."

Cook had a full list of needed reforms, ranging from downsizing the jail population by stopping the practice of using it to hold state and federal prisoners, to creating adequate programming for health care and treatment within the jail, to decreasing the number of people held as pretrial detainees. "We need pretrial diversion, bail reform, and cite and release policies to hold down the jail population," he argued. "There needs to be the political will to do this. It's a crime to jail a kid when there is a choice, and there are many other choices. And we ought to be treating drug abuse as a public health issue, not a law enforcement issue."

The prospects look gloomy. "It is going to take enlightened leadership, and I see only a glimmer of hope for that," said Cook. "But we are not giving up. The state juvenile justice system is finally undergoing reforms because of pressure from families and activists, and I think it will take the same sort of effort to fix things at the adult level and here in New Orleans, at the parish level. That is already happening here with the OPP Reform Coalition, the Safe Streets people, and all that."

But there is a long, long way to go in New Orleans.

This work by StoptheDrugWar.org is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International

Add new comment