|

Feature:

Afghan

Opium

Farmers

Caught

in

the

Squeeze

10/7/05

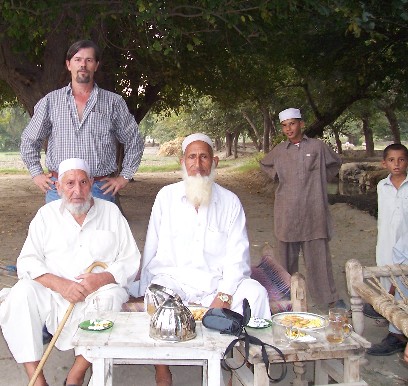

With opium responsible for somewhere between 40-60% (depending on whom you ask; the United Nations figure is 52%) of Afghanistan's Gross Domestic Product, the poppy and its derivatives, particularly heroin, are indisputably the backbone of the national economy. But with Afghan President Hamid Karzai, backed by the United Nations and the Western powers, calling for a holy war against opium planting and trafficking, the country's estimated 350,000 poppy farmers are finding themselves caught in a squeeze. On one hand, growing the poppy provides farmers, as well as an estimated 500,000 landless laborers, with the means of feeding their families. On the other hand, farmers risk losing their crops and the year's harvest profits as the national government's eradication efforts swing into gear.

"The government said don't grow the poppy," Isef told DRCNet, "but they didn't give us anything; they just came to destroy. When they destroyed our poppies, they took away the benefits we got from them, so we don't grow them anymore." At first, the elders said they weren't growing opium because they wanted to do what the government asked, but upon further questioning it became clear that it was not civic-mindedness but the cruel fact of crop eradication that drove the village out of the opium economy. "When they eradicated, we lost our money," said Kaul. "The government promised they would pay, but they didn't pay us, they just came and destroyed. They are big liars." Neither has the district received any assistance from the international community, said the elders. "We have no school here, no clinic, no hospital," complained Isef. Asked if their children play sports, the elders sneered and said no, the only sport they have is chasing animals. "We don't have enough water," Isef continued. We tried building dikes of clay, but they are washed away in one day. We don't have water pumps. The government does not help us and neither do the foreigners," he said. Growing opium poppies has benefits for farmers and for the Afghan state, said William Boyd, a senior economic advisor on Afghanistan for the World Bank, as he addressed the Senlis Council symposium on licensing the opium crop last week. "The poppy provides incomes and livelihoods for farmers and laborers," he said. "It is a coping mechanism for the rural poor. On the national level, the poppy crop supports the balance of payments and stimulates aggregate demand. The reason economic growth is so buoyant in Afghanistan is the funds from opium." But while farmers and the national economy benefit from the illicit poppy crop, it also has deleterious consequences, Boyd said. "Because the opium economy is so important and attractive, it tends to raise wages and other costs, thus making it more difficult for the economy to expand in other areas. The opium economy distorts the rural economy and society, and you can see its effects in everything from land prices to bride prices," he explained. The negative effects of the prohibited opium trade are also felt at the level of national institutions, said Boyd. "You have the corruption and poor governance associated with a large-scale illegal activity, and you have a nexus with insecurity, warlordism, and a weak state," he said. But while the illicit trade has negative consequences, so do efforts to eradicate the crop, the economist argued. "If you look at Nangahar province, you see that production is down dramatically, but it has had a harmful impact on the local economy," he said. "People are leaving for Pakistan."

Under pressure from eradicators, the poppy crop has moved to more remote areas, said Isef. "There are farmers who still grow around here, but they are in the high mountains. It is good for them because they don't have any money and it is the only way for them to buy food." The pattern described by Isef and Kaul is also being played out at the national level. While the UN Office on Drugs and Crime reported that the Afghan acreage devoted to the poppy crop had decreased by 22% this year, production remains not only substantial but fluid and responsive to outside pressures and local support. According to the UNODC, opium cultivation has shifted from traditional centers, such as Nangahar, Badakshan, and Helmand provinces, toward more fertile areas in the north and west of the country where warlords allied with the government reign. "How do you explain the collapse of cultivation in the province of Nangahar and the enormous increases in key provinces such as Balkh and Farah?" where production more than tripled over last year, asked UNODC director Antonio Maria Costa in a statement late last month. Much depends on the commitment of local governors, some of whom remain linked to the drug trade, he said. "Corruption is the wild card, and we have got to remove it from the deck." But for farmers like Isef and Kaul, it's not corruption that is the problem, but lack of assistance. "If we had some help, we could improve productivity," said Isef. "We need help with new breeds of rice, with seeds, with fertilizers. If the government wants to provide help for us, good, but we don't expect it. We made good money growing opium, but now we don't grow it anymore because the government will destroy it." Isef and Kaul and the villagers they represent may have been driven out of the business, but the local industry continues to thrive, said an opium trader in nearby Jalalabad. "Business is good," he said, as he showed off pound-sized balls of opium. "There is always someone who wants to sell and someone who wants to buy," he told DRCNet. That means that neither eradication nor help for the farmers will stem the opium trade.

PERMISSION to reprint or redistribute any or all of the contents of Drug War Chronicle (formerly The Week Online with DRCNet is hereby granted. We ask that any use of these materials include proper credit and, where appropriate, a link to one or more of our web sites. If your publication customarily pays for publication, DRCNet requests checks payable to the organization. If your publication does not pay for materials, you are free to use the materials gratis. In all cases, we request notification for our records, including physical copies where material has appeared in print. Contact: StoptheDrugWar.org: the Drug Reform Coordination Network, P.O. Box 18402, Washington, DC 20036, (202) 293-8340 (voice), (202) 293-8344 (fax), e-mail drcnet@drcnet.org. Thank you. Articles of a purely educational nature in Drug War Chronicle appear courtesy of the DRCNet Foundation, unless otherwise noted.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||