Political Leaders

Nice People Take Drugs

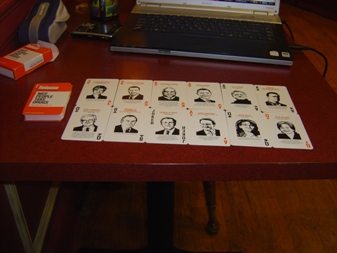

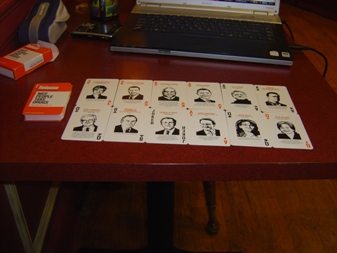

In June we highlighted a bus advertising campaign, "Nice People Take Drugs," conducted by the British drug reform advocacy group Release. Some of the nice people from Release attended the big drug policy conference in Albuquerque last week, and they were nice enough to give us one of their new "Nice People Take Drugs" decks of playing cards, featuring politicians from the US, UK and elsewhere and the quotes they've given about their past drug use. (Whether all of the featured politicians are nice people is a subjective question, of course.) The front of the cards feature the organization's web site and a toll-free helpline, hard to see in the picture (0845 4500 215 if you're in Britain and need the help).

Albuquerque's "British Invasion" also featured the Transform Drug Policy Foundation's new publication, After the War on Drugs: Blueprint for Regulation. Check Drug War Chronicle later this week for a conference report highlighting this and more.

Here's a sampling of the Release cards:

Last but not least, for now, a picture I snapped during the conference's closing plenary, former New Mexico Governor Gary Johnson delivering the keynote:

Last but not least, for now, a picture I snapped during the conference's closing plenary, former New Mexico Governor Gary Johnson delivering the keynote:

Last but not least, for now, a picture I snapped during the conference's closing plenary, former New Mexico Governor Gary Johnson delivering the keynote:

Last but not least, for now, a picture I snapped during the conference's closing plenary, former New Mexico Governor Gary Johnson delivering the keynote:

Resignation of Mexico's Attorney General Won't Change Much

I have an invited comment online at JURIST, explaining why the resignation of Mexican Attorney General Eduardo Medina Mora won't change much. (Hint: It's Prohibition.)

JURIST, which is published at the University of Pittsburgh School of Law, is "the world's only law school-based comprehensive legal news and research service," according to its FAQ. It's also free, archives included. I've already added it to my Google Reader.

Why Isn't the Drug War a Mainstream Political Issue?

Pete Guither has a typically observant post noting the lack of serious drug policy discussion among top-tier political bloggers:

Why then is America's political culture so desperate to avoid discussing this issue? Pete argues correctly that both parties have been so consistently bad on drug policy that neither side has moral standing to condemn the other. He's talking about bloggers, but this idea has broad implications. So long as both parties remain essentially comfortable wasting billions in tax dollars on a failed drug control strategy, there is no incentive to exhaust political capital challenging the status quo.

D.C. radio personality Kojo Nnamdi offered a complementary theory this morning on NPR, which I find equally helpful. Referencing the same excellent Washington Post story mentioned in Pete's post, Nnamdi suggested that politicians realize something is wrong, but are unsure what else to propose. There's a lot to this when you consider how ignorant most politicians are about the finer points of the war on drugs. As obvious as it is to many of us that progress can't occur until the drug war ends, this conversation is dark territory for a politician with aggressive enemies and a flimsy grip on the subject matter. Nor are they eager to familiarize themselves with an issue that lacks apparent traction and is perceived (often erroneously, but still) as politically suicidal.

Reformers struggle to explain how we'll overcome these obstacles, and I'm skeptical of anyone who thinks they've figured it out. Our watershed moment will arrive, I believe, through events beyond our control. Recent discussion of the drug war's role in financing terror provides just one example of how new priorities can raise doubts about the old ones.

The future will bring many unexpected changes, but it will never redeem drug prohibition and its infinitely corrupting, ruinous legacy. I don't know what it will take to finally put this horrible war on trial, but I'm certain we'll find out.

Obviously, to drug policy reformers, the war on drugs is one of the critical issues of our time -- it affects everything, from criminal justice and fundamental Constitutional rights to education to foreign policy to poverty and the inner cities, and on and on.Worse yet, the reluctance of established political blogs to enter the drug policy debate is dwarfed by the longstanding refusal of mainstream journalists and politicians to do so. Drug reporting in the mainstream press is an ongoing abomination, with exceptions so rare that they provoke widespread fascination when they occur.

So it can be baffling to note the degree to which serious discussions about the drug war tend to be missing from the major political blogs on the right and the left.

Why then is America's political culture so desperate to avoid discussing this issue? Pete argues correctly that both parties have been so consistently bad on drug policy that neither side has moral standing to condemn the other. He's talking about bloggers, but this idea has broad implications. So long as both parties remain essentially comfortable wasting billions in tax dollars on a failed drug control strategy, there is no incentive to exhaust political capital challenging the status quo.

D.C. radio personality Kojo Nnamdi offered a complementary theory this morning on NPR, which I find equally helpful. Referencing the same excellent Washington Post story mentioned in Pete's post, Nnamdi suggested that politicians realize something is wrong, but are unsure what else to propose. There's a lot to this when you consider how ignorant most politicians are about the finer points of the war on drugs. As obvious as it is to many of us that progress can't occur until the drug war ends, this conversation is dark territory for a politician with aggressive enemies and a flimsy grip on the subject matter. Nor are they eager to familiarize themselves with an issue that lacks apparent traction and is perceived (often erroneously, but still) as politically suicidal.

Reformers struggle to explain how we'll overcome these obstacles, and I'm skeptical of anyone who thinks they've figured it out. Our watershed moment will arrive, I believe, through events beyond our control. Recent discussion of the drug war's role in financing terror provides just one example of how new priorities can raise doubts about the old ones.

The future will bring many unexpected changes, but it will never redeem drug prohibition and its infinitely corrupting, ruinous legacy. I don't know what it will take to finally put this horrible war on trial, but I'm certain we'll find out.

Pagination

- First page

- Previous page

- …

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- …

- Next page

- Last page