The United States military is melding counterinsurgency with counternarcotics missions in Afghanistan in what officials called "a basic strategy shift" in its Afghan campaign. Up until now, the US military has shied away from anti-drug operations in Afghanistan, leaving them to the DEA, the British, and Afghan authorities in a bid to avoid alienating Afghan peasant populations dependent on the poppy crop for an income.

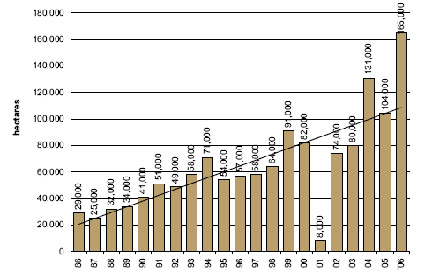

But with Afghan opium production at an all-time high last year and predicted to go even higher this year -- Afghanistan accounted for 92% of the global opium supply in 2006 and will account for close to 100% this year--despite nearly a billion dollars in US anti-drug aid, officials in Washington have decided after long discussion that the Afghan drug war must be ratcheted up.

The new policy was announced in a new report US Counternarcotics Strategy for Afghanistan released last week and rolled out at an August 9 State Department briefing by Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP--the drug czar's office) head John Walters and Acting Assistant Secretary of State for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Thomas Schweich.

"We know that opium, maybe second only to terror, is a huge threat to the future of Afghanistan," said Walters. "The efforts by the Afghan people to build institutions of justice and rule of law are threatened not only by the terror, but the drug forces that are both economic, addictive and, of course, support in some cases terror, not only through money, but through influence and moving people away from the structures of government toward the structures of drug mafias and violence," he said.

The new strategy is a combination of carrots and sticks, heavily weighted toward the sticks. Out of the $700 million budgeted for anti-drug activities this year, only about $120 million to $150 million will go to alternative development, with the remainder dedicated to eradication, interdiction, building up the Afghan criminal justice system, and going after high-level traffickers.

Some $30 million will go to farming communities that agree to give up poppy production, but this is a pittance compared to the $3.1 billion the trade is estimated to be worth, or even the roughly $700 million estimated to end up in the hands of peasant farmers. While most of the incentive money will go to the north, where production is down, the more Taliban-friendly east and southeast will get forced eradication and increased efforts to go after high-level traffickers. Ambassador Schweicher qualified the tougher approach as "substantially harsher discincentives" for those areas. And the US military will be involved.

What exactly that means remains unclear. At the August 9 briefing, Walters dodged repeated questions about the exact nature of US military involvement. "We expect a more permissive environment for these operations, given the plans and commitments here," Walters said. "Again, what -- your question was what counter-narcotics operations is the military going to do. That's not what this is doing, is saying the military is going to become the eradication force or the interdiction force. What we're going to do is create -- we've now created, we believe, the structures to allow counter-narcotics operations, whether they're arrests of people by Afghans, whether they're interdiction, whether they're eradication to be integrated into the security effort that's going on."

It might work, but there are gigantic obstacles in the way, said Raheem Yaseer of the Center for Afghan Studies at the University of Nebraska-Omaha. Improving the security situation is critical, said Yaseer.

"The bombers and the Talibans are crossing the border from Pakistan with all these weapons and getting across the checkpoints and getting in among the villagers, where they shoot at the allied forces. Then the allies bomb the villages, and that creates a lot of resentment, and the people won't listen to the allies," he said. "The US can track a bullet crossing the border, but they can't find the Talibans," he said, a note of frustration in his voice.

Alternative development could attract peasant farmers if the security situation were stabilized, he said. "It's the bigger warlords and drug lords who are the problem," Yaseer argued. "And yes, there are some high government officials, big shots, involved in drug trafficking, too. All of them have been nourished by this money for years and don't want to see it go away. But ordinary people would be satisfied with a little money because they know growing poppies is condemned by their tradition and religion."

Endemic corruption is another problem. Even anti-drug aid and alternative development assistance is likely to be siphoned off, said Yaseer. "The corruption is very deep, and a lot of money will vanish into people's pockets. You have to watch the people at the top, too, or it won't be effective," he said. "You'll only be spending money uselessly."

Congressional leaders called the new strategy a "welcome recognition" that new initiatives had to be hatched to address the Afghan opium problem, but worried that it wasn't enough. "What the plan lacks is the recognition that Afghanistan is approaching a crisis point, and that immediate action is required to eliminate the threat of drug kingpins and cartels allied with terrorists so we can reverse the country's steady slide into a potential failed narco-state," said House Foreign Affairs Committee chair Rep. Tom Lantos (D-CA) and ranking minority member Rep. Ileana Ros-Lehtinen (R-FL) in a statement responding to the new strategy.

Lantos and Ros-Lehtinen aren't the only members of Congress concerned. Others have called for an entirely different approach. Following the lead of the French defense and drug policy think tank the Senlis Council, which has been calling since 2005 for licensing the poppy crop, Rep. Russ Carnahan (D-MO) has suggested licensing Afghan farmers to grow the crop for legal pain medications, similar to the way the international community diminished the drug trafficking problem in India and Turkey. Senator John Sununu (R-NH) has suggested the US buy opium crops from the farmers and destroy them. Senator Joe Biden (D-DE) has suggested switching the focus away from poor farmers and toward disrupting the cartels that are moving the drugs.

But the drug czar and the State Department explicitly rejected licensing as an impractical "silver bullet" that would not work and have similarly rejected proposals to buy up the crop. And they will definitely be going after poor farmers as well as high-level traffickers.

But more of the same isn't going to do the trick, said the Drug Policy Alliance. "The so-called 'carrot and stick' approach has failed in every country it has been tried in, including our own," said Bill Piper, the group's director of national affairs. "As long as there is a demand for drugs, there will be a supply to meet it. Drug prohibition makes plants more valuable than gold."

More of the same may even make matters worse, Piper argued. "The US is dangerously close to turning Afghanistan into the next Iraq," said Piper. "Forced eradication of opium crops is driving poor Afghans into the hands of our enemies, strengthening the Taliban, and feeding the insurgency there. The war on drugs is undermining the war on terror and pushing Afghanistan to the brink of civil war."

The Bush administration has belatedly figured out it has a very serious problem in Afghanistan. The question now is whether this vigorous new strategy will calm the situation or only inflame it.

Comments

Re-Legalized Marijuana will put a dent in Terrorist Funding

Here's my latest video:

Why Lou Dobbs Should Support Marijuana Legalization

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9VKf5YfQb7s&eurl=http%3A%2F%2Fwww%2Enewagecitizen%2Ecom%2F

Other related readings:

Drug Policy

The MERP Project

The Marijuana Re-Legalization Policy (MRP) Project

http://www.newagecitizen.com/ReLegalization01.htm

http://www.newagecitizen.com/editorial_on_the_marijuana_re.htm

How Continuing the Drug War could make Nuclear Terrorism a Reality

by Bruce W. Cain

http://www.newagecitizen.com/Editorials/v8n1NuclearTerrorism.htm

Add new comment